04. WHOSE HEALTH IS MOST VULNERABLE TO CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS?

Susan Higgins, Alexandra Adams, Margaret Eggers, with contributing authors Lori Byron, Paul Lachapelle, Sally Moyce, Richard Ready, Lisa Richidt, Jennifer Robohm, and Eliza Webber,

Some people are more vulnerable to climate change impacts than others. When considering all Americans, Gamble et al. (2016) identify those at higher risk to include children, older adults, pregnant females, tribal communities, communities of color, people with lower incomes, and people living in rural or remote regions. People with disabilities or mental health conditions, as well as people who are displaced, suffer from social isolation, or live without insurance are also more likely to suffer adverse consequences from climate change (Forman et al. 2016). Montanans fit into a number of the categories just noted, as we describe below.

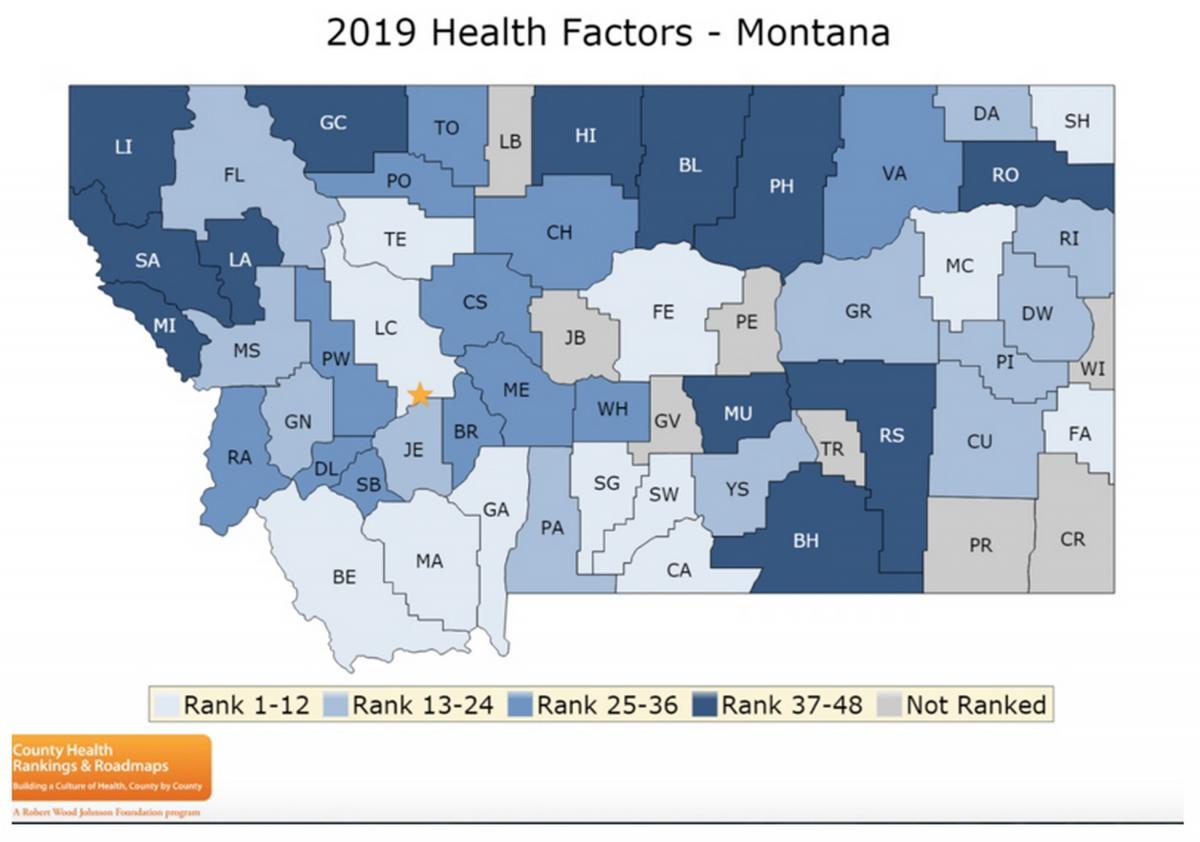

We recognize that some people in Montana are already health-challenged with issues like chronic disease, poor diet and nutrition, and/or limited access to food and healthcare, regardless of climate change impacts. Such challenges are depicted annually for nearly every county in the United States in the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps report (Givens et al. 2019). Figure 4-1 shows how Montana’s 56 counties rank with respect to a set of health factors that determine how long and how well we live. Those factors—e.g., personal behavior, socioeconomic status, and the physical environment—strongly influence health concerns resulting from climate change.

We find ten sectors of Montana’s population are at particular risk of having their health impacted by Montana’s warming climate. We base that assessment on an understanding of our state’s warming climate (Whitlock et al. 2017; also see Section 2), known climate impacts on human health (see Section 3), and Montana’s health profile, as follows.

Montana’s Health Profile

Before describing Montanans who are most vulnerable to climate-related health concerns, we acknowledge our state’s current health profile. A health profile describes access to and availability of health resources, social and demographic characteristics, current health status, health risk factors, and quality of life (Durch et al. 1997). Montana has many health-related inequities and complexities, as described below, even before adding climate-related complications.

Montana is a rural state

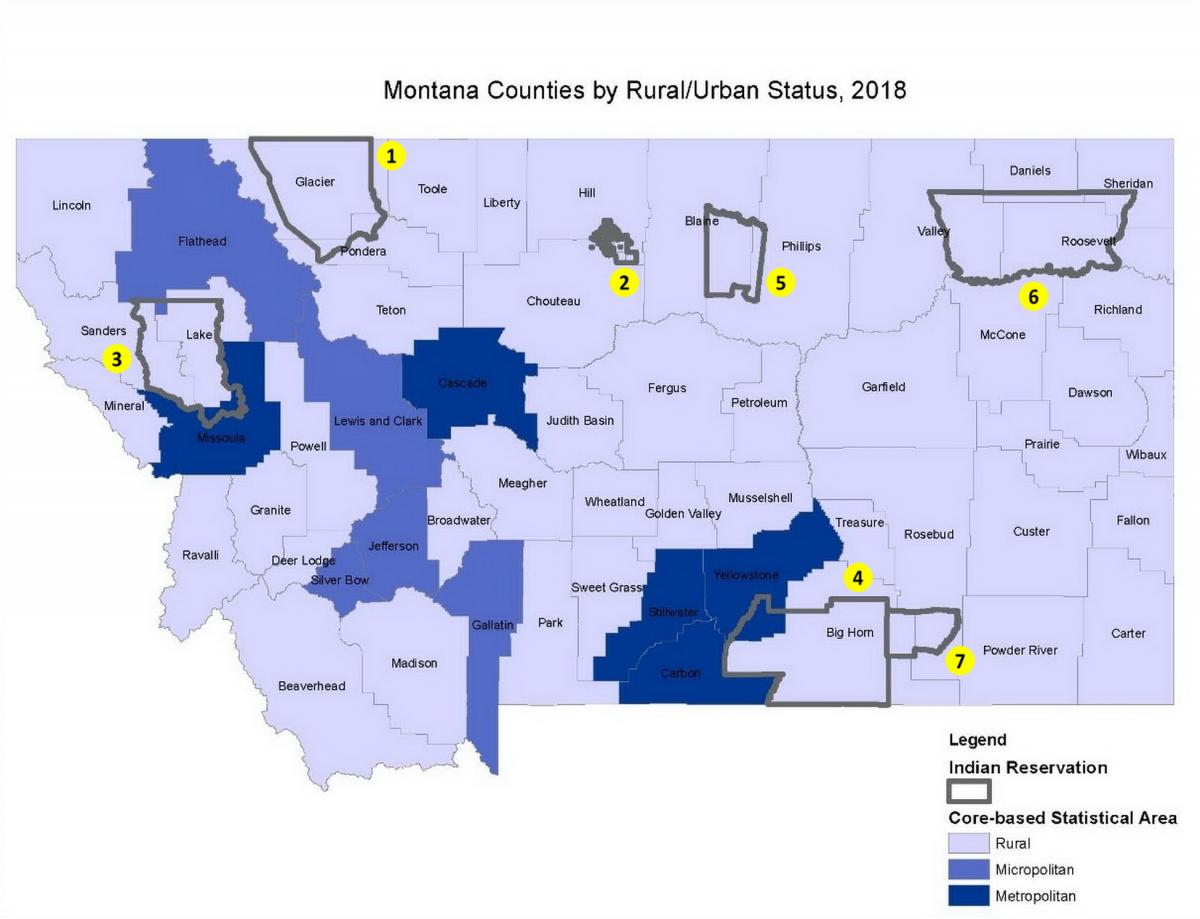

The most important aspect of Montana’s health profile is that Montana is a rural state. As such, many Montanans live in frontier areas[1] that lack essential services like healthcare, and thus must travel long distances for such vital needs. Figure 4-2 shows the population status of Montana’s 56 counties, and the boundaries of tribal reservations (OMB 2010).

Montana averages just 6.9 people/mile2 (2.7 people/km2), making it the third most sparsely populated state in the country (US Census Bureau 2010). The 2018 census estimates show that 33.1% of Montana’s 1,062,305 residents live in rural areas, as defined by Office of Management and Budget’s Core-Based Statistical Areas (OMB 2010; US Census Bureau 2018b). In comparison, just 5.6% of the total US population resides in a rural area (US Census Bureau 2018b). Montana’s population is 88.9% White. American Indians comprise 6.6% of Montana’s population, one of the highest percentages of any state (US Census Bureau 2018c). Other ethnic and racial groups represent 4.6% of the population.

The most important aspect of Montana’s health profile is that Montana is a rural state. As such, many Montanans live in frontier areas that lack essential services like healthcare, and thus must travel long distances for such vital needs.

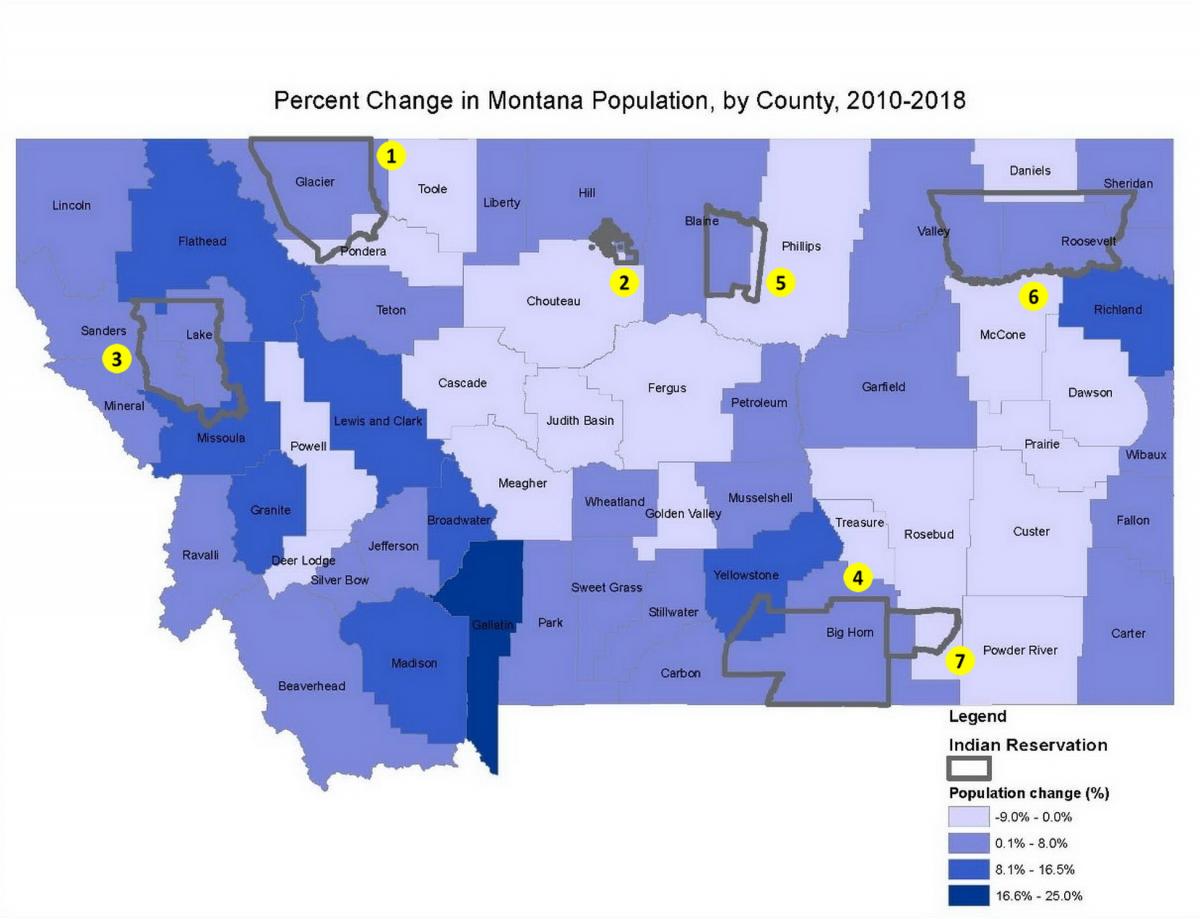

Between 2010 and 2018, Montana’s population grew 7.4%, faster than the average national growth rate of 5.9% during the same period. Yet, even though Montana as a whole is growing quickly, its rural areas continue to lose numbers: 18 of 56 counties lost population (US Census Bureau 2018d). Growth has been concentrated in Montana’s most highly populated counties, with urban county growth in Gallatin, Yellowstone, Flathead, Missoula, and Lewis and Clark counties accounting for 83% of the state’s total population increase (US Census Bureau 2018d) (Table 4-1; Figure 4-3).

|

Table 4-1. Distribution of Montana population growth, 2010-2018a |

||||

|

Location |

Net Growth |

Growth share (%) |

Urban / rural status |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Montana net growth, statewide |

72,890 |

|

|

|

|

Growth share by county |

22,363 |

30.7 |

Urban |

|

|

a Data sources: US Census Bureau 2018b,d b Combined net growth of the following rural counties: Beaverhead, Big Horn, Blaine, Broadwater, Carter, Chouteau, Custer, Daniels, Dawson, Deer Lodge, Fallon, Fergus, Garfield, Glacier, Golden Valley, Granite, Hill, Judith Basin, Lake, Liberty, Lincoln, Madison, McCone, Meagher, Mineral, Musselshell, Park, Petroleum, Phillips, Pondera, Powder River, Powell, Prairie, Ravalli, Richland, Roosevelt, Rosebud, Sanders, Sheridan, Sweet Grass, Teton, Toole, Treasure, Valley, Wheatland, and Wibaux c Combined net growth of the following urban counties: Carbon, Cascade, Jefferson, Silver Bow, and Stillwater |

||||

Health-wise, where you live matters

It is not surprising that healthcare access is a challenge to Montanans in low-population counties and—combined with other risk factors described below—translates into poorer health outcomes when compared to those living in high-population counties. Montana ranks higher than the national average in percentages of people over the age of 65, housed in mobile homes, without health insurance, or with disabilities (Headwaters Economics 2019). Thirty-three percent of adults in Montana report having two or more chronic health conditions, and the prevalence of multiple chronic conditions is significantly higher among adults living in low-population counties (MTDPHHSa undated).

Health outcomes for Montana’s American Indian communities are worse than for its non-American Indian communities. For example, the rate of premature death in Montana is much higher for American Indians than for non-Native residents (MTDPHHS 2019a). The life expectancy for Montana American Indians is nearly 20 yr less, and their rates of death from cancer, injury, cirrhosis, diabetes, and heart disease are higher than for non-Native residents (MTHCF undated). Table 4-2 compares the differences in health outcomes for Montana’s different ethnic and racial groups (Givens et al. 2019). These inequities stem from systemic, long-standing issues such as racism, historical trauma, and rural isolation; and/or lack of access to healthy foods and healthcare, inadequate water and wastewater infrastructure, problems of safety or crime, loss of tribal connections, high stress levels, and poverty. In addition, funding disparities for education, housing, healthcare, and food have perpetuated this vulnerability (US Commission on Civil Rights 2003, 2018).

|

Table 4-2. Differences in health outcome measures among counties and racial/ethnic groups in Montana (Givens et al. 2019) |

|||||||

|

|

Healthiest MT county |

Least healthy MT county |

AI/AN a |

Asian/PI a |

Black |

Hispanic |

White |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Premature death b |

4900 |

21,000 |

19,400 |

2900 |

10,000 |

6800 |

6600 |

|

Poor or fair health (%) |

11% |

26% |

25% |

NA |

NA |

18% |

13% |

|

Poor physical health (days/month) c |

3.0 |

5.4 |

5.1 |

NA |

NA |

3.4 |

3.3 |

|

Poor mental health (days/month) c |

2.9 |

4.5 |

5.3 |

NA |

NA |

4.6 |

3.4 |

|

Low birth weight (%) |

5 |

7 |

9 |

10 |

12 |

8 |

7 |

|

------- |

|||||||

Key health issues in Montana

The CDC (2017) identified the leading causes of death in Montana as respiratory disease, heart disease, accidents, suicide, cancer, and stroke. Building from that knowledge, Montana’s State Health Improvement Plan identified five priority areas for healthcare focus (MTDPHHS 2020a). We summarize each of the priority areas below, plus compare Montana to the national averages in Table 4-3. All declarations in the bullets that follow, unless otherwise credited, are derived from Montana’s State Health Improvement Plan (MTDPHHS 2020a).

- Behavioral health, including suicide prevention, depression, substance abuse, and opioid misuse.—Suicide-related deaths in Montana are the fourth highest per capita in the US, and almost twice the national average (CDC 2018). This rate is significantly higher in rural counties and in American Indian populations. Precursors to suicide often include depression and/or substance abuse. The number of adults treated with mental illnesses in Montana between 2009 and 2013 was higher than the national average, and nearly 64,000 Montana adults struggle with substance abuse. Alcohol is the most commonly abused substance in Montana, but opioids are the leading cause of drug-overdose deaths in Montana, accounting for 44% of such deaths.

- Chronic disease.—Chronic diseases are long-term conditions lasting one or more years that require ongoing medical attention or limit activities of daily living (NCCDPHP 2019). Chronic disease in Montana is attributable in large part to smoking, obesity, poor nutrition, and physical inactivity. Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death, with 1600 tobacco-related deaths each year. Per capita, these deaths strike Montana’s American Indian population disproportionately (Campaign for Tobacco-free Kids 2017). Two factors adding to chronic disease in our state are a) 75% of Montana adults and 72% of youth do not meet the national physical activity recommendations (MTOPI 2019); and b) only 62% of Montanans are up-to-date with colorectal cancer screening (MTDPHHS 2016).

- Maternal health and newborns.—Approximately 12,000 live births occur each year in Montana. Infant mortality in Montana is 5.7 per 1000 births for White populations, closely matching the rate for all races nationally of 5.8 per 1000 births. In great contrast, infant mortality for American Indians in Montana is 10 per 1000 births (MTDPHHS 2017).

- Motor vehicle crashes.—Motor vehicle crashes are one of the most common causes of fatal and non-fatal injuries in Montana. In 2014, the rate of death due to crashes was 19.4 per 100,000 in Montana, approaching twice the national figure of 10.3 per 100,000 in the same year (MTPHIS undated). The rate is higher among American Indians and for those living in rural versus urban areas (MTDPHHSb undated). From 2011–2016, 60% of all crash-related fatalities involved a driver impaired by alcohol or drugs (MTDPHHS 2020a).

- Adverse childhood experiences.—The Centers for Disease Control defines adverse childhood experiences as (CDCb undated):

…potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years) such as experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence in the home; and having a family member attempt or die by suicide. Also included are aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding such as growing up in a household with substance misuse, mental health problems, or instability due to parental separation or incarceration of a parent, sibling, or other member of the household.

Adverse childhood experiences are directly related to negative outcomes in chronic disease, substance abuse, and mental health. In 2011, 60% of Montana adults reported having one or more adverse childhood experiences (CDCb undated). Due to the established links between adverse childhood experiences and negative behavioral and health outcomes, this is an important area for health improvement in our state (CDCc undated). People with higher probability of chronic disease and mental health issues related to adverse childhood experiences are also more vulnerable to climate-related health impacts.

|

Table 4-3. Comparisons of Montana and US rates for incidence of five priority health issues. See text for a description of each issue. |

||||

|

Priority health issue in Montana |

Unit of measue |

Montana |

US |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suicide mortalitya |

per 100,000 population |

28.9 |

14.0 |

|

|

Chronic diseaseb |

% of adults with multiple (two or more) chronic conditions |

33.2% |

25.7% |

|

|

Infant mortalityc |

per 1000 live births |

5.4 |

5.8 |

|

|

Motor vehicle crash mortalityd |

per 100,000 population |

17.1 |

11.2 |

|

|

Adverse childhood experiencese |

% of adults experiencing one or more such experiences |

60% |

61.5% |

|

|

Data sources (all accessed 4 April 2020) |

||||

Populations Vulnerable to Climate Change

Review of Montana’s health profile reveals that our state’s rural nature—including limited access to healthcare facilities—has a wide-reaching impact on our citizens’ well-being. Montanans suffer from chronic disease, inadequate maternal and childhood healthcare, a high rate of vehicular deaths, and mental illness, suicide, alcoholism, and substance use disorders. We next consider what concerns result when climate-related impacts are added to these existing health conditions. The remainder of this section describes ten groups in Montana having particular health vulnerabilities to climate change.

People with existing chronic conditions

Why it matters.—People living with chronic conditions (e.g., asthma, obesity, heart disease, pulmonary disease) are more vulnerable to the risks of climate change (Gamble et al. 2106). Extreme heat and degraded air quality that result from wildfires greatly aggravate these existing health problems (USEPA 2016).

What we know in Montana.— Rural Montanans, regardless of race or ethnicity, have higher mortality rates for six of the ten leading causes of death, including heart disease, diabetes, and chronic liver disease, compared to residents of more urban counties. Rural risk factors for health disparities in Montana include geographic isolation, fewer healthcare providers, more health risk behaviors (e.g., binge drinking and unhealthy diets), lower socioeconomic status, and limited employment opportunities. The story becomes even more stark when considering Montana’s American Indian communities. From 2011 to 2015, for example, the median age at death in Montana was 16 and 19 yr younger for American Indian men and women, respectively, when compared to their non-Native counterparts (MTDPHHS 2019a).

People threatened by increased heat

Why it matters.—National data show that increasing heat negatively impacts mental health and risk of heat stroke (see Section 3). People without access to shade, air conditioning, and cooling places are at much greater risk than those having adequate protection from heat. In addition, heat exposure during pregnancy carries with it the risk of premature births and birth defects (Ravanelli et al. 2019; Section 3).

What we know in Montana.—Increased heat poses the greatest risk for migrant agricultural workers and others working outdoors, as well as those living in inadequate housing (without, for example, adequate insulation or air conditioning).

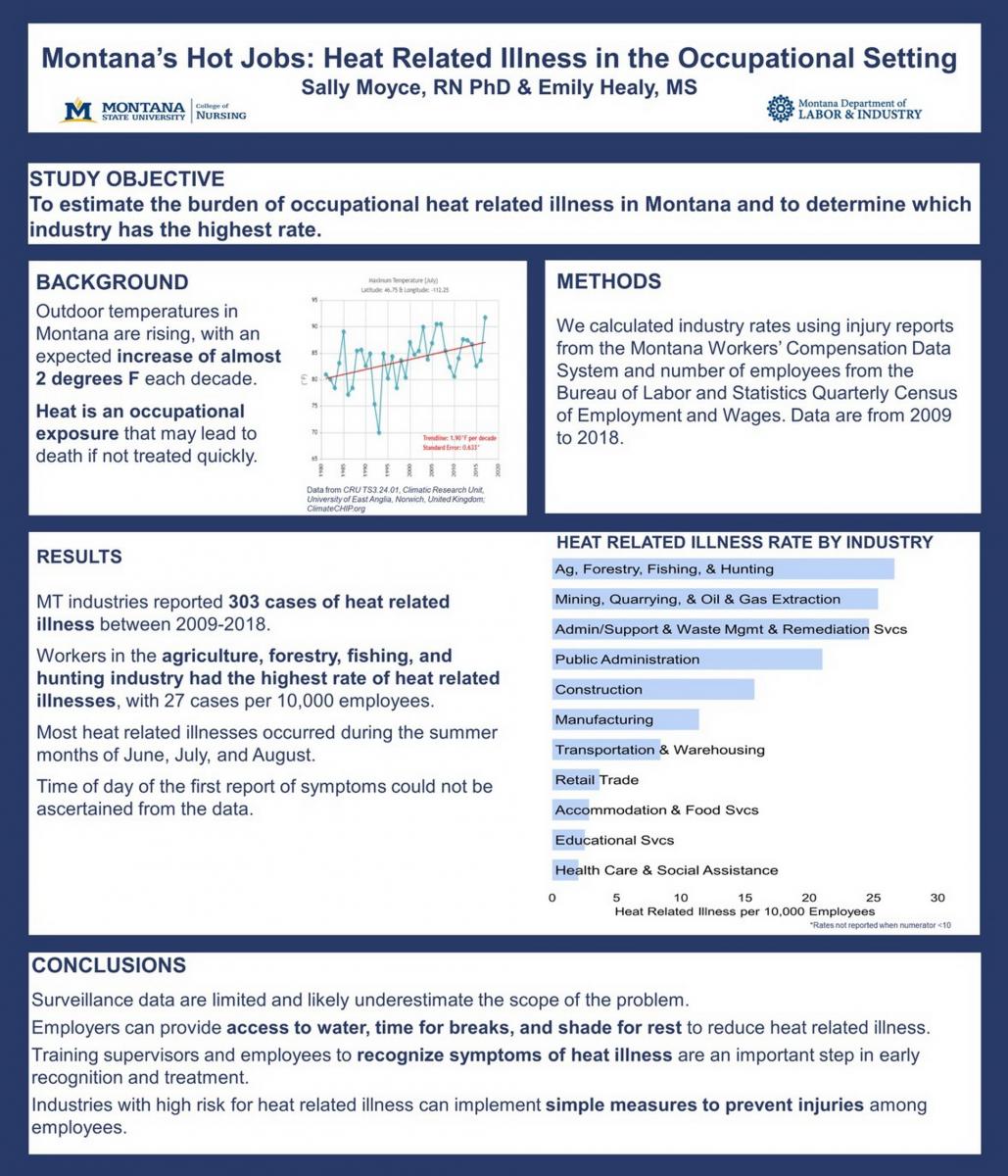

- Those working in the outdoors.—Over 62% of Montana lands are in farm and ranch production (NASS 2019). In summer, farmers, ranchers, and workers labor outside on these lands through the heat of the day. Researchers are exploring the impacts of heat on agricultural and other outdoor occupations. For example, migrant and seasonal workers come to Montana to work in agriculture, construction, and other industries involving outdoor labor. These workers are at increased risk due to inadequate or substandard housing facilities, cultural and linguistic isolation, lack of health insurance, and poverty. As depicted in Figure 4-4, fatalities are highest in the occupational sector that includes agriculture and forestry (North American Industry Classification Sector 111). An analysis of workers' compensation data revealed that workers in these industries are at particular risk of injuries on high heat days (Moyce and Nealy 2019).

- Housing and air conditioning.—Inhabitants of mobile homes may be more susceptible to higher heat days.[2] Some mobile homes may be unbearably hot in summer if they lack adequate air conditioning and/or insulation. In 2017, there were 45,496 mobile homes in Montana, or 10.8% of the total housing units, which is nearly double the national average of 5.7% (Headwaters Economics 2019). In addition, mobile homes are more likely to be damaged during extreme storms, which poses a risk for both the structure and its occupants.

Data on air conditioning in Montana are sparse. Based on a small-sample survey, NEEA (2012) estimates that 19% of rural Montana households and 35% of urban households have some type of air conditioning (NEEA 2014). People living in urban areas tend to have central air conditioning systems, while those in rural areas tend to have window or roof units.

People living in proximity to wildfire and smoke

Why it matters.—Particulate matter from wildfire smoke impacts incidence of lung disease and asthma (see sidebar). Smoke and fire damage can also cause or accentuate depression and anxiety. Montanans living in or near areas prone to wildfire are most vulnerable, although smoke travels great distances. Section 3 provides more information on health effects of wildfire and smoke.

What we know in Montana.—The wildland-urban interface is where human development and wildlands meet or intermingle, placing houses or other structures near or within fire-prone forests. In 2010, 64.1% of Montana houses were located in the wildland-urban interface (Martinuzzi et al. 2015), the second highest percentage of all western states behind Wyoming. In Montana’s 25 western counties, located in forested areas and for which contiguous fire hazard data are available, over 10% of homes are in high fire hazard, forest interface areas (Headwaters Economics 2018). Houses and structures in such areas are at highest risk of burning, with the risk decreasing the more distant houses are from the wildland-urban interface.

The 2017 Seeley Lake Fires and Lung Function

Higher incidence of wildfire due to climate change is resulting in more large wildfires (Whitlock et al. 2017). Emergency room visits and hospitalizations for cardiovascular and respiratory complaints have increased due to wildfire smoke exposures. As exposures to wildfire increase in number and intensity, research on the resulting health impacts becomes more vital (Reid et al. 2016; Black et al. 2017).

In a local example, Orr et al. (2020) found long-term respiratory complications resulting from wildfires around the town of Seeley Lake, Montana. For 49 days in 2017, Seeley Lake was exposed to smoke from multiple nearby wildfires (NPR 2019). A group of 95 participants from Seeley Lake (average age 63 yr) was administered spirometry, a test used to assess how well the lungs work by measuring amount and rate of air inhaled and exhaled.

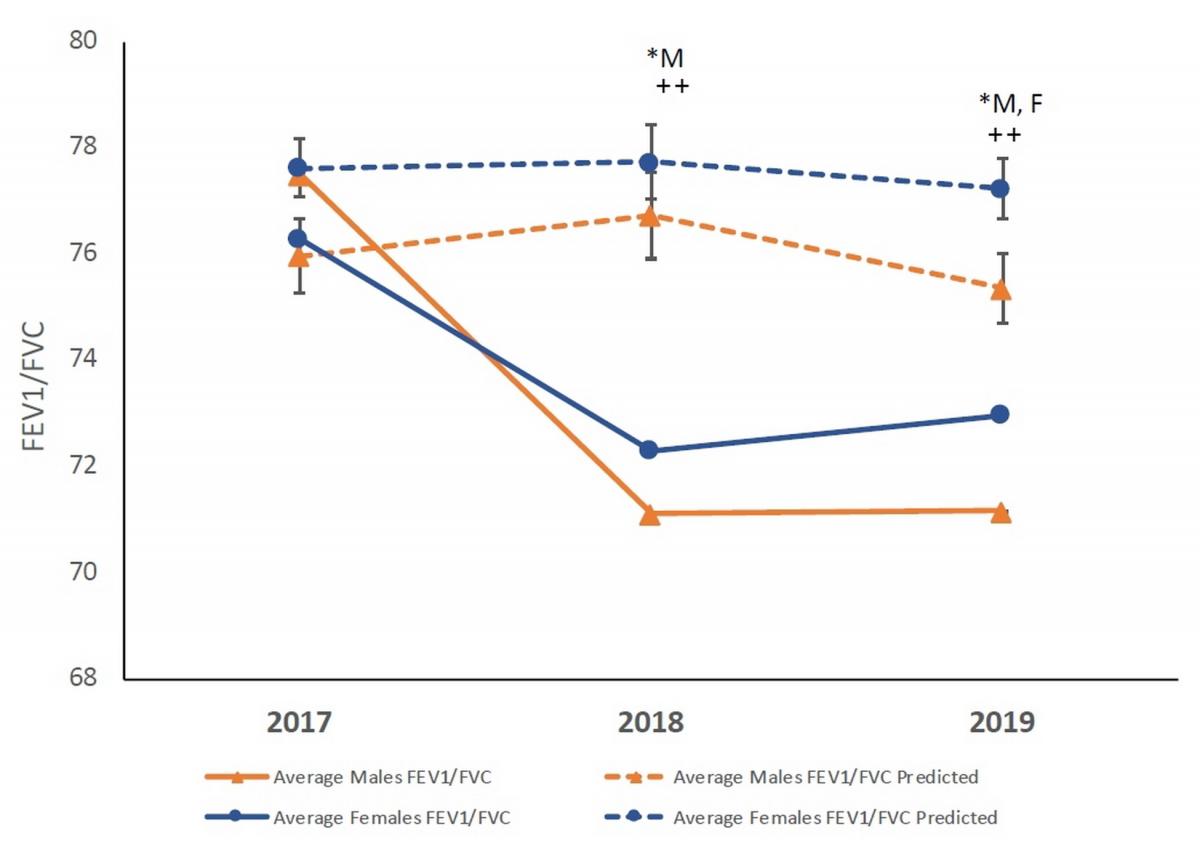

Pulmonary function changes from predicted values. The graph depicts the changes to lung function (FEV1/FVC) in 2018 and 2019 following the Rice Ridge fire in Seeley Lake, Montana. In both years following the exposure the observed (solid lines) was significantly lower than predicted (dashed lines) for males (*M), while significantly lower in 2019 for females (*F). In addition, the male values were significantly lower as compared to the observed values in 2017. (* P<0.05 observed vs predicted within sex; P<0.01 Significant compared to 2017 for corresponding group)

A decrease in lung functiona was observed over time. Specifically, measured lung capacity decreased significantly compared with predicted values (age and sex matched), with a greater effect on males. The effect appears to continue at least two years post exposure. These observed decreases highlight the need for longitudinal studies to assess the health effects of smoke exposures.

---

a The ratio of FEV1/FVC, shown as the y-axis in the plot, is a measure of the amount of air a person can forcefully exhale from their lungs.

People facing food and water insecurity

Why it matters.—Montanans face the stark reality of losing nutritious—and for some, indigenous—foods due to wildfires, drought, and flood events resulting from climate change. Drought and flood can diminish local crop yields and floods can carry and distribute crop diseases. Drinking water supplies, likewise, can be threatened, first due to diminished water availability during drought, and second due to public water and wastewater disruption and potential for water-borne pathogen spread during flooding. Home wells that are inundated can become contaminated, thereby posing a health risk. Aging water infrastructure is also an issue. For example, one of the five 100-year-old concrete drop structures in the St. Mary Canal failed in 2020 flooding, making it impossible to divert water from the canal into the Milk River (Havre Daily News 2020). This canal supplies up to 80% of the water to communities along the Hi-line and northeastern Montana, and this loss of conveyance greatly threatens irrigation and municipal water supplies.

Regarding food security, only about 10% of the food we consume in Montana is grown here (Montana Department of Agriculture 2013). Thus, our food security is threatened by climate changes outside of Montana, a fact that strengthens the need for increasing local food production and processing. The USDA’s Federal-State Marketing Improvement Program (USDA undated) and many instate partners (e.g., agriculture departments, agricultural experiment stations, universities) are working to improve Montana’s food supply chains among producers, processors, food services, grocers, pantries, and distributors to assure food availability and improve instate production to support local needs.

What we know in Montana.—In 2017, 42,745 (10.2% of total) households received food stamps from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program[3]; 19,564 (4.7% of total) received Supplemental Security Income[4]; and 8696 (2.1% of total) received cash public assistance income (Headwaters Economics 2019).

Nearly 10 percent of Montanans struggle with hunger, and 37,000 children live in food-insecure homes. Thirty of Montana’s 56 counties have areas considered food deserts, i.e., low-income areas where at least 500 people and/or 33% of the residents must travel more than 10 miles (16 km) to the nearest supermarket (or 1 mile [1.6 km] in urban areas). This equates to nearly 72,000 Montanans without fresh, affordable food on a daily basis (Montana Food Bank Network undated).

Nearly 10 percent of Montanans struggle with hunger, and 37,000 children live in food insecure homes. Thirty of Montana’s 56 counties have areas considered to be food deserts, i.e., low-income areas where at least 500 people and/or 33% of the residents must travel more than 10 miles (16 km) to the nearest supermarket (or 1 mile [1.6 km] in urban areas). This equates to nearly 72,000 Montanans without fresh, affordable food on a daily basis (Montana Food Bank Network undated).

Most Montanans (86%) get their drinking water from public water supplies and most public water systems meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s Safe Drinking Water Standards (MTDEQ undated). Still, the MCA (Whitlock et al. 2017; also see Section 2) describes multiple threats to Montana’s domestic water supply, including drought, flooding, and extreme storm events; and also to Montanans using domestic wells susceptible to contamination from flood events. MCA also states that Montana will experience reduced snowpack and diminished late-season flows with changing climate. Both are critical to public and private water supplies, as well as agricultural production and, hence, food security[5].

Tribal members in Montana are observing impacts from climate change on traditional foods and water sources. For the Crow Tribe, warming streams are affecting the distribution and health of fish species. Multiple berry shrub species and other traditionally harvested plants are also impacted (Doyle et al. 2013; Martin et al. 2020). Devastating spring floods inundated the Crow Reservation in 2007 and 2011, the latter of which set a gaging station record and damaged more than 200 homes (Billings Gazette 2011a,b). Lacking the resources to remediate the problems caused by the floods, many families had to move back into damaged and now mold-infested homes, in spite of health risks (Martin et al. 2020).

Interviews with both Native and non-Native low-income residents of the Flathead Indian Reservation in northwestern Montana found that half reported being food insecure or having inconsistent access to adequate food. About 28% of those interviewed hunt, fish, and/or gather wild foods such as berries, and on average were more food secure than those who did not. Fish, game, and wild plants were valued for their taste, freshness, nutritional value, and traditional significance, as well as for promoting self-sufficiency. These residents perceive that their local wild foods are being adversely impacted by climate change, particularly by wildfires and increased seasonal variability in precipitation and temperature (Smith et al. 2019).

People who are very young, very old, or pregnant

Why it matters.—Beginning at the fetal development stage, exposures to air or water pollution can increase the risk of impaired brain development (Clifford et al. 2016), stillbirth (Siddika 2016), and preterm births (Peterson et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2015). Infants and children are disproportionately affected by toxic exposures because they eat, drink, and breathe more in proportion to their body size (Heindel et al. 2016; Anderko et al. 2020). In addition, children spend more time outdoors, putting them at greater risk for respiratory problems from airborne particulates, wildfire smoke, and allergens. Children are also more sensitive to infectious diseases brought on by natural disasters that compromise water sanitation (Balbus and Malina 2009; Cooley et al. 2012).

Mental and developmental health issues also impact the young. For example, Clayton et al. (2014) suggest that young people may face increased risk of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder from extreme climate-driven weather events. Studies have shown that early-childhood health status also influences health and socioeconomic well-being later in life (Anda and Brown 2010; Currie et al. 2014).

Advanced age is a top risk factor related to illness or death from extreme heat (CDCa undated) due to hormonal changes and health issues that make thermoregulation and hydration more difficult (Brennan et al. 2019). In addition, the likelihood of chronic disease increases with age (Prasad et al. 2013). The elderly are more likely to have preexisting medical conditions such as diabetes, pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure, all of which will be exacerbated by the higher temperatures expected with climate change. For example, the elderly often have compromised mobility that reduces their ability to respond to natural disasters. Given chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (and other chronic diseases), the elderly are also highly susceptible to air pollution, such as ground-level ozone, particulate matter, or dust associated with drought, wildfires, and high-wind events (Bell et al. 2014).

When faced with extreme heat, pregnant women can be subject to preterm labor, and their babies may be smaller and/or more prone to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome/Sudden Unexpected Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS/SUIDS; also see Section 3). Women are less tolerant of extreme heat during pregnancy. They are more sensitive to dehydration and acute kidney damage.

What we know in Montana.—In 2018, according to the Montana Public Health Information System, Montana had 11,515 births (MPHIS undated). In the same year. 5.9% of children in Montana were younger than 5 yr old, similar to the US average. Montanans 65 yr and older made up 18.7% of the population, compared to 16.0% nationwide. The proportion of people 65 yr and older is even higher in rural counties, where they are at risk due to limited access to healthcare (see below). In the six most populous counties, 16.8% of residents are 65 yr and older, while in rural counties, 21.7% are 65 and older (US Census Bureau 2019).

People with limited access to healthcare services

Why it matters.—Extreme weather events and natural disasters limit access to medical care. It is all too common for Montanans to be snowed in at their rural homes, with days passing before plows can get through. In February 2018, for example, 20-ft snow drifts were reported on the Blackfeet Reservation, and a state of emergency was declared by the Tribal Council and Montana Governor Bullock (Great Falls Tribune 2018; Spokesman-Review 2018). Likewise, rapid spring flooding, sometimes combined with major precipitation events, can cut communication lines, block access to roads, and limit availability of medical services to those in remote areas. The town of Roundup experienced such flooding of the Musselshell River in the spring of 2011, resulting in closed roads and disruptions to potable water supply (City of Roundup undated).

The inability to access medical providers following such extreme events is particularly consequential for those who already have compromised health (MTDPHHS 2020a). In rural Montana, assistance can be greatly delayed, given lack of nearby community health services and/or the transportation infrastructure needed to reach medical attention.

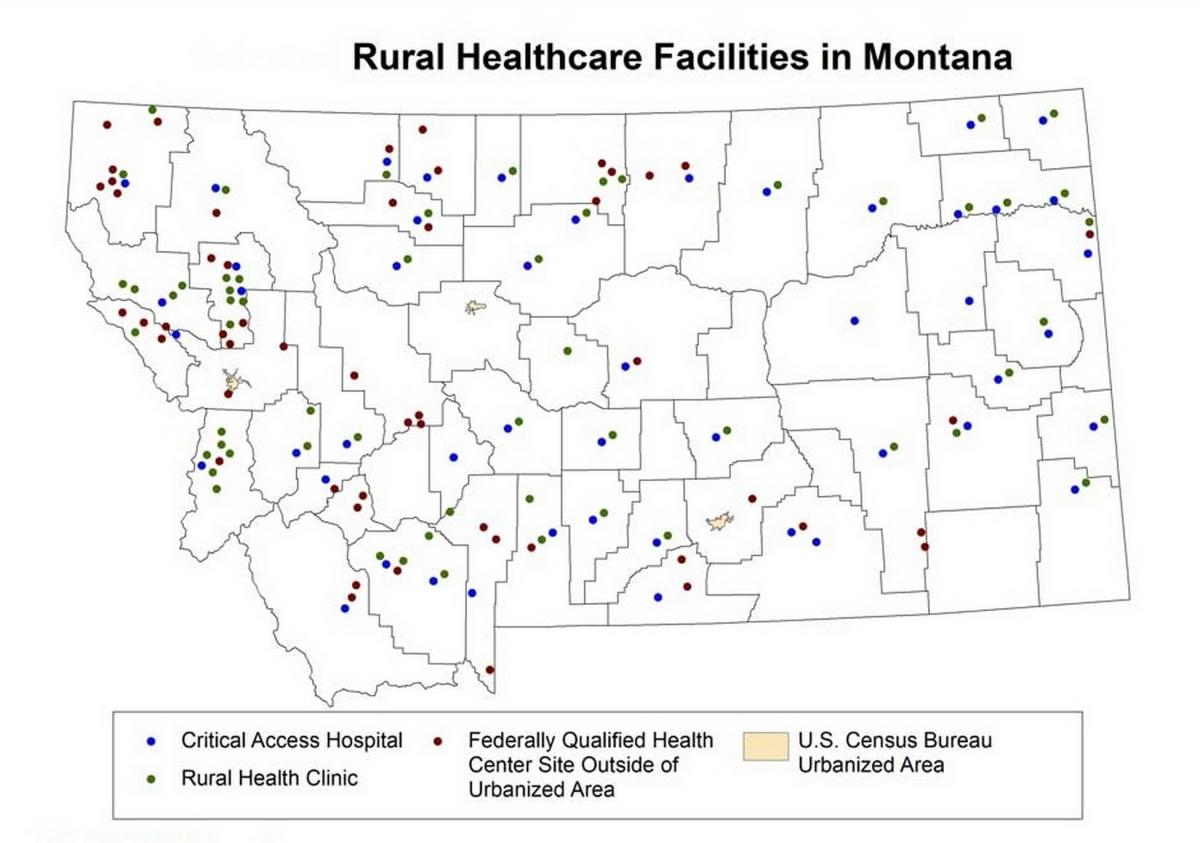

What we know in Montana.—As of January 2020, Montana had 49 critical-access hospitals, 58 rural health clinics, and 52 federally qualified health centers located outside of urban areas (Figure 4-5) (RHIhubb 2018). Even with these facilities, annual survey studies of Montana community members by the Montana Office of Rural Health show that access to healthcare is a major concern (MORHAHEC 2017). The Federal Health Resources and Services Administration designates 23 of Montana’s 56 counties as Health Provider Shortage Areas, meaning residents have limited access to primary care providers (HRSA undated). Such a designation is based on provider-to-patient ratio, percentage of the population living in poverty, and travel time to the nearest health facility.

In 2019, residents of rural counties had a mortality rate 1.5 times higher due to unintentional injury compared with residents of more urban counties. Rural-county residents also had higher death rates due to chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, heart disease, diabetes, and suicide compared with residents of more urban counties, in part due to lack of immediate access to healthcare providers (MTDPHHS 2020a). The impact of climate change—whether on disease outcomes or transportation infrastructure—will only exacerbate the existing challenge of providing adequate access to health services for rural Montanans.

People living in poverty

Why it matters.—To save money, families with low incomes often must make lifestyle choices that subject them to impacts of climate change. These tough choices can result in poor diet, inadequate shelter, delayed medical care, unhealthy housing with leaks and mold, and no funds for electric fans or air conditioners. People in poverty often live in substandard housing or in mobile homes and are more vulnerable to heat-related illnesses and extreme weather events (Headwaters Economics 2019). Displaced communities are also at risk. Planning is especially critical for counties and communities already suffering from the loss of coal jobs and coal tax revenue, who need to diversify their economies in addition to planning for impacts described in this report.

What we know in Montana.—The poverty rate in Montana is similar to the US average. In 2017, 14.4% of Montana residents lived below the federally defined poverty level compared to 14.6% nationally. However, a mean of 17.6% of young Montana residents under 18 yr lived in poverty, with highest percentages in more rural and reservation regions. The poverty rate for Montana residents 65 yr and older was 8.3% (US Census Bureau 2018e; Givens et al. 2019), and 9.2% for the US residents over 65 (CRS 2019).

American Indians

Why it matters.—American Indians are among the most vulnerable groups to climate change (Ford 2012; Bennett et al. 2014; Gamble et al. 2016; Ebi 2018). As the Third National Climate Assessment’s section on Indigenous Peoples explains (Bennett et al. 2014):

Native cultures are directly tied to Native places and homelands, and many indigenous peoples regard all people, plants, and animals that share our world as relatives rather than resources. Language, ceremonies, cultures, practices, and food sources evolved in concert with the inhabitants, human and non-human, of specific homelands.

Hence, in addition to coping with long-standing economic, social, and political inequities, tribes are stressed by climate changes that threaten ways of life they have practiced for thousands of years. Native communities’ cultural and spiritual reliance on local ecosystems, water sources, and subsistence foods contributes to an increased vulnerability during extreme climate events (Cozetto et al. 2013; Gamble et al. 2016). The US Global Change Research Program’s 2016 report summarizes climate impacts to the health of Native peoples under the themes of loss of cultural identity, water insecurity, decreased food safety and security, and degraded infrastructure (Gamble et al. 2016).

What we know in Montana.—Interviews with Crow Tribal Elders reveal that climate change impacts to wild foods, water quality, and traditional spiritual practices are already being observed (Doyle et al. 2013; Doyle and Eggers 2017; also see sidebar). Crow Elders express a widespread sense of environmental-cultural-health loss, along with despair at their inability to address root causes of these local impacts of climate change (Martin et al. 2020). On the Flathead Indian Reservation, more than a quarter of low-income residents surveyed (both Native and non-Native) increase their food security by harvesting wild foods. They perceive that these wild foods are already adversely impacted by climate changes, such as increased wildfires, increased drought, and weather variability (Smith et al. 2019).

Communities nationwide face threats to water security from droughts, floods, and other extreme climate events. Those threats are uniquely serious for tribes as many aquatic species are culturally and nutritionally vital to their well-being (Donatuto et al. 2011; Cozetto et al. 2013; Doyle et al. 2013). As an example, for many Crow families, increased microbial contamination means that rivers have been lost as a source of trusted water for ceremonial drinking and bathing (Doyle et al. 2013). Addressing degraded water and wastewater infrastructure is always challenging (Ferguson et al. 2011; Ojima et al. 2013; Redsteer et al. 2011), but the maze of jurisdictional and legal complexities—for example, the lack of authority to create water districts as described by the Apsaalooke Water and Wastewater Authority (Crow Reservation, Montana)—makes it more difficult for tribes (Doyle et al. 2018). In response, several Montana tribes are proactively assessing current and projected climate change impacts, developing resiliency plans, and implementing adaptation strategies (see sidebar in Section 5).

Changes Rippling Through Our Waters and Lives

C. Martin, J. Doyle, J. LaFrance, M.J. Lefthand, S.L. Young, E. Three Irons, and M. Eggers

The Crow Reservation is located in south central Montana, in the heart of our traditional homelands. As we live in a wide-open landscape and are tied to a different time than the fast pace of western life, our understanding of nature and observations of the seasons comes from the eye instead of a calendar or watch.

Climate change is already impacting our lands, our waters, our health and well-being. To better understand these impacts, we interviewed 26 Crow Elders about their perceptions of changes in local weather patterns and ecosystems throughout their lifetime, and how they are being affected. We conducted a thematic analysis of the interviews.

Interviewees’ observations paralleled and elaborated on instrumental climate data: we are experiencing far less snowfall and milder winters, increased spring flooding, hotter summers, and more severe wildfire seasons. Additionally, many Elders commented on extreme, unusual, and unpredictable weather events, compared to earlier times when the seasons were consistent year after year.

Interviews notably identified declines in wild foods, which have not been recorded by scientists; wild game, fish, berries, and medicinal plants are being detrimentally affected in diverse ways (Martin 2020). Our homes and infrastructure have been hit time after time by high floods; we have few resources to repair the damage, so this is taking a toll on families, including on our health and well-being.

In addition to ecosystem resource losses and changes, we are devastated by the loss of coal jobs and coal tax revenue. More than 1200 coal mining and tax-funded jobs have been lost in the past couple years, in a community of about 8000 people. Without that income and lacking any other tax structure, we cannot adequately fund our government nor maintain our infrastructure.

Through the research we have been conducting on climate change and with our Tribal Elders, we are able to better understand what has been happening and anticipate what is to come. Although we are enduring unprecedented environmental change and extreme economic conditions, we are looking for solutions we can implement ourselves.

---

For more detail, see Martin et al. (2020).

People lacking adequate health insurance

Why it matters.—Access to health insurance is directly related to a person’s ability to respond to health emergencies. People with chronic health conditions but no health insurance are less likely to be able to manage their illnesses, putting them at greater risk should an emergency arise (Sommers et al. 2017). Those without health insurance, for example, suffer more consequences from air pollution compared to those with health insurance (Cooley et al. 2012). Likewise, other climate-related concerns such as water-borne disease will be more difficult to treat for those without health insurance.

What we know in Montana.—In 2017, 91.5% of Montana residents had either private or public health insurance, close to the national average of 93.1% (Table 4-4). However, the proportion of Montana residents with health insurance varies both by age and between rural and urban places. Almost all residents old enough to qualify for Medicare have health insurance. The percent of residents with health insurance is higher in urban counties than in rural counties. However, private insurance prices vary, and coverage may be costly with plans paying for 60-90% of medical expenses. This variability may leave some individuals and families with substantial out-of-pocket costs depending on their plan (HealthCareInsider 2020).

|

Table 4-4. Percentage of Montana residents with health insurance in 2017 (US Census Bureau undated). |

||||

|

Residency |

Age group |

19-64 yr |

65 yr and older |

All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All counties |

94.2% |

88.1% |

99.4% |

91.5% |

|

Six most populous counties |

96.1% |

90.0% |

99.4% |

92.9% |

|

All other counties |

91.5% |

84.9% |

99.4% |

89.5% |

People with mental health issues

Why it matters.—People living with and learning about the consequences of climate change can experience stress, anxiety, and deep feelings of loss (Clayton et al. 2017). A 2019 Yale report found that 62% of Americans were "somewhat worried” and 23% were “very worried” about global warming (Leiserowitz et al. 2019). The Yale Program on Climate Change Communications (YPCCC 2019) estimates that 60% of Montanans worry about climate change.

Chronic conditions like depression and anxiety can be worsened by climate change, with consequences ranging from minimal stress to clinical conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts (USGCRP 2016). Feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, fatalism, apathy, and denial associated with environmental change have become so prevalent as to have earned their own descriptive terms, including climate grief, eco-anxiety, and solastalgia (Albrecht et al. 2007; Clayton et al. 2017; NBC News 2018; Time 2019).

Such mental strife can be heightened further for those whose economic livelihoods or traditional ways are closely tied to the land or environment, as well as those who hunt, fish, and gather wild foods. That group includes people working in natural resource-related industries, for example agriculture, forestry, and tourism, as well as coal, oil, or natural gas extraction (Clayton et al. 2017; also see sidebars—adjacent and in Section 3).

Mental Health Impacts on Resource-dependent Communities

Dr. Julia Haggerty, Associate Professor, Geography/Earth Sciences Department, Montana State University

Decarbonizing at national and global scales has profound social, economic, and, by extension, health implications for local places that have developed as key nodes in the current energy system. In Montana, these sites include the communities in which energy extraction, processing, and/or distribution constitute the area’s primary source of public revenue and private income.

Resource-dependent communities are at risk of acute mental-health concerns in the event of mass layoffs associated with plant closures and other events in the contraction of energy economies. Research shows that negative psychological outcomes associated with such events derive primarily through economic hardship (Broman et al. 1990), and secondarily through the loss of occupational identity (Carley et al. 2018). Given that Montana’s remote and rural areas are chronically underserved across a variety of critical healthcare services, available resources may prove inadequate in the face of abrupt economic transitions.

Resource-dependent communities are at risk of acute mental-health concerns in the event of mass layoffs associated with plant closures and other events in the contraction of energy economies. Research shows that negative psychological outcomes associated with such events derive primarily through economic hardship (Broman et al. 1990), and secondarily through the loss of occupational identity (Carley et al. 2018). Given that Montana’s remote and rural areas are chronically underserved across a variety of critical healthcare services, available resources may prove inadequate in the face of abrupt economic transitions.

Where local government revenue depends heavily on fossil fuel extraction—as in the case of several American Indian reservations as well as some rural communities—the very services necessary to build community resilience in the face of economic shocks are at risk (Besser 2013; Haggerty et al. 2018). In the very worst cases in recent history in the US, abandonment of resource-dependent regions can create a host of chronic health issues associated with the compounding effects of persistent rural poverty, environmental contamination, and the legacy of hazardous work conditions (Hendryx 2009).

What we know in Montana.—From 2011–2015, Montana’s suicide rate, at 240 suicides each year, was nearly twice the US average (MTDPHHS 2019b). Alarmingly, the suicide rate in Montana rose 38 percent from 1999 to 2016. In 2017, Montana had the highest suicide rate in the US, but in 2018 the state dropped to the fourth highest (AAS 2020a,b). Montana regularly registers one of the highest suicide rates in the country, with an age-adjusted suicide rate of 25.9 per 100,000 people in 2016 compared to almost half that rate for the US. Males are 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide than females. Others at risk are veterans, American Indians, and residents of rural counties.

Substance use is a risk factor for suicide, with toxicology screenings revealing that over 40% of suicides involve alcohol use.

Attempted suicide in Montana is also alarming. One in 10 of all Montana high school students attempted suicide in 2019. For American Indian high school students alone, 1.5 in 10 attempted suicide in 2019 (MOPI 2019).

Governor Bullock of Montana, reacting at least in part to these grave realities, invested $80 million over five years to address mental health services (MTDPHHS 2020b).

Along with the mental health issues shared by many across Montana, tribal members may suffer a unique type of personal anguish, one tied to tribal history, which changes brought by climate change can exacerbate. In a study conducted primarily by Crow tribal members, 26 Tribal Elders were interviewed about the impacts of climate change on local ecosystems and community health. Nearly all participants described a sense of loss in relation to the impacts from changing climate and environmental conditions on their land. They write (Martin et al. 2020):

For us, and perhaps for many other indigenous people, the changes aren’t simply unfamiliar alterations in our home environment causing discomfort—they are direct threats to our ability to carry on the traditional practices which define us as a people. It is history repeating itself in an even more insidious way. We lost the majority of our lands through treaties and Congressional acts. We lost generations of raising and educating our own children through federal boarding schools starting in the 1880s. We have since lost the upper Bighorn River to Yellowtail Dam, agricultural and recreational lands to non-tribal members, much of our traditional diet—the list goes on. Now, even though we live in our traditional territory, the changes in climate are changing our homelands all around us, and this time there is no single enemy to fight.

What conclusions can we draw?

As described in Section 2, Montana will experience more 90oF+ (32oC+) heat days, increased wildfires, more spring flooding, and less water available with more drought during the late growing season (Whitlock et al. 2017). Given this knowledge, communities need to take action now to protect the health of Montana residents most vulnerable to impacts of climate change. Climate change will amplify vulnerability, exacerbating pre-existing health disparities. The next section provides recommendations for how Montana communities (including city, state, and tribal governments), healthcare practitioners and facilities, and individual community members can respond today to address the impacts of climate change on our most vulnerable populations.

[1] A frontier area is defined as having fewer than 7 people/mile2 (2.7 people/km2) (RHIhuba 2020).

[2] Mobile homes are defined by the Montana Department of Revenue as any trailer, house trailer, or trailer coach that is over 8 ft wide or 45 ft long and designed to be moved by connecting to another vehicle, or under 8 ft wide or 45 ft long and used as a principal residence (Montana Department of Revenue undated).

[3] The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides benefits to people who are elderly, homeless, unemployed, have low or no income, or are disabled with low incomes. Recipients can purchase groceries with SNAP benefits.

[4] Supplemental Security Income (SSI) gives financial assistance to people who are disabled, aged, or blind and of limited income. Unlike Social Security benefits, SSI benefits are not determined by the recipient’s lifetime earnings.

[5] Food security, as defined in the glossary of this report, describes an individual or community’s ability to reliably access a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food.

Literature Cited

Albrecht G, Sartore G-M, Connor L, Higginbotham N, Freeman S, Kelly B, Stain H, Tonna A, Pollard G. 2007. Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry 15(Suppl 1):S95-8. doi:10.1080/10398560701701288.

[AAS] American Association of Suicidology. 2020a. Annual ranking of USA states by crude suicide rates (rates per 100,000 population), 1990-2018 [report]. Available online https://suicidology.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/StateRankings1990to20.... Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

[AAS] American Association of Suicidology. 2020b. USA suicide: 2018 official final data [report]. Available online https://suicidology.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2018datapgsv2_Final.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Anda RF, Brown DW. 2010. Adverse childhood experiences and population health in Washington: the face of a chronic public health disaster. Results from the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [report prepared for the Washington State Family Policy Council]. 131 p. Available online http://www.wvlegislature.gov/senate1/majority/poverty/ACEsinWashington20.... Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Anderko L, Chalupka S, Du M, Hauptman M. 2020. Climate changes reproductive and children’s health: a review of risks, exposures, and impacts. Pediatric Research 87:414–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0654-7.

Balbus JM, Malina C. 2009. Identifying vulnerable subpopulations for climate change health effects in the United States. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 51(1):33-7. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318193e12e.

Bell ML, Zanobetti A, Dominici F. 2014. Who is more affected by ozone pollution? A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 180(1):15–28.

Bennett TMB, Maynard NG, Cochran P, Gough R, Lynn K, Maldonado J, Voggesser G, Wotkyns S, Cozzetto K. 2014. Indigenous Peoples, Lands, and Resources [chapter 12]. In: Melillo JM, Richmond TC, Yohe GW (eds). 2014.Climate change impacts in the United States: the Third National Climate Assessment. Washington DC: US Global Change Research Program. p 297-317. Available online https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/highlights/report-findings/indigenous-p.... Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Besser TL. 2013. Resilient small rural towns and community shocks. Journal of Rural and Community Development 8(1). Available online https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/725/163. Accessed 28 May 2020.

Billings Gazette. 2011a (Jun 4). Historic floods: old-timers make comparisons with epic 1978 flood [article]. Available online https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/old-timers-m.... Accessed 11 May 2020.

Billings Gazette. 2011b (Jun 15). Crow flooding: more than 200 Crow Reservation homes damaged, destroyed from flooding [article]. Available online https://rapidcityjournal.com/news/more-than-crow-reservation-homes-damag.... Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

Billings Gazette. 2012 (Nov 1). Montana wildfires burn most acreage since 1910; $113M spent to battle blazes [article]. Available online https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/montana-wild.... Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

Black C, Tesfaigzi Y, Bassein JA, Miller LA. 2017. Wildfire smoke exposure and human health: significant gaps in research for a growing public health issue. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 55:186–95.

Brennan M, O’Keeffe ST, Mulkerrin EC. 2019. Dehydration and renal failure in older persons during heatwaves-predictable, hard to identify but preventable? Age and Ageing 48(5)615–8.

Broman CL, Hamilton VL, Hoffman WS. 1990. Unemployment and its effects on families: evidence from a plant closing study. American Journal of Community Psychology 18(5):643-59.

Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. 2017. The toll of tobacco in Montana [website]. Available online https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/problem/toll-us/montana. Accessed 13 May 2020.

Carley S, Evans TP, Konisky DM. 2018 (Mar). Adaptation, culture, and the energy transition in American coal country. Energy Research and Social Science 37:133-9.

[CDCa] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. undated. Frequently asked questions about extreme heat [website]. Available online https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/extremeheat/faq.html. Accessed 23 Mar 2020.

[CDCb] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [undated]. Violence prevention: preventing adverse childhood experiences [website]. Available online https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/ind.... Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[CDCc] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [undated]. Violence prevention: behavioral risk factor surveillance system ACE data [website]. Available online https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/ace.... Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. National Center for Health Statistics: stats of the state of Montana [website]. Available online https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/states/montana/montana.htm. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

[CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. National Center for Health Statistics: Suicide mortality by state [website]. Available online https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/suicide-mortality/suicide.htm. Accessed 26 Mar 2020.

City of Roundup. [undated]. Floods of 2011 [website]. Available online http://www.roundupmontana.net/flood-2011.html. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Clayton S, Manning C, Krygsman K, Speiser M. 2017. Mental health and our changing climate: impacts, implications, and guidance [report]. Washington DC: American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica. 70 p. Available online https://www.apa.org/images/mental-health-climate_tcm7-215704.pdf. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Clayton S, Manning CM, Hodge C. 2014. Beyond storms and droughts: the psychological impacts of climate change [report]. Washington DC: American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica. 51 p. http://ecoamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/eA_Beyond_Storms_and_Dr.... Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Clifford A, Lang L, Chen R, Anstey KJ, Seaton A. 2016. Exposure to air pollution and cognitive functioning across the life course—a systematic literature review. Environmental Research 147:383-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.018.

Cooley H, Moore E, Heberger M, Allen L. 2012 (Jul). Social vulnerability to climate change in California [report]. Prepared for the California Energy Commission Pub; report #CEC-500-2012-013. 77 p. Available online https://ww2.energy.ca.gov/2012publications/CEC-500-2012-013/CEC-500-2012.... Accessed 13 May 2020.

Cozetto K, Chief K, Dittmer K, Brubaker M, Fough R, Souza K, Ettawageshik F, Wotkyns S, Opitz-Stapleton S, Duren S, Chavan P. 2013. Climate change impacts on the water resources of American Indians and Alaska Natives in the US. Climatic Change 120:569–84. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0852-y.

[CRS] Congressional Research Service. 2019 (Jul 1). Poverty among Americans aged 65 and older [report]. Report #R45791. Washington DC: CRS. 23 p. Available online https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45791.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

Currie J, Zivin JG, Mullins J, Neidell M. 2014. What do we know about short- and long-term effects of early-life exposure to pollution? Annual Review of Resource Economics 6(1):217-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100913-012610.

Donatuto JL, Satterfield TA, Gregory R. 2011. Poisoning the body to nourish the soul: prioritizing health risks and impacts in a Native American community. Health, Risk, and Society 13(2):103-27. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.556186.

Doyle JT, Redsteer MH, Eggers MJ. 2013. Exploring effects of climate change on Northern Plains American Indian health. Climatic Change 120(3):643–55. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0799-z.

Doyle JT, Eggers MJ. 2017. Crow climate observations [sieebar]. In: Whitlock C, Cross WF, Maxwell B, Silverman N, Wade AA. 2017 Montana Climate Assessment. Bozeman and Missoula MT: Montana State University and University of Montana, Montana Institute on Ecosystems. P 23-26. Available online http://montanaclimate.org/. Accessed 13 May 2020.

Doyle JT, Kindness L, Realbird J, Eggers MJ, Camper AK. 2018. Challenges and opportunities for tribal waters: addressing disparities in safe public drinking water on the Crow Reservation in Montana, USA. International Journal of Environmental Research in Public Health 15(4):E567. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040567.

Durch JS, Bailey LA, Stoto MA, eds. 1997. Measurement tools for community health improvement process [chapter 5]. In: Improving health in the community: a role for performance monitoring. Washington DC: National Academies Press, Institute of Medicine, Committee on Using Performance Monitoring to Improve Community Health. Available online https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK233011/#ddd00101. Accessed 14 Apr 2020.

Ebi KL, Balbus JM, Luber G, Bole A, Crimmins A, Glass G, Saha S, Shimamoto MM, Trtanj J, White-Newsome JL. 2018. Tribes and indigenous people [chapter 15]. In: Reidmiller DR, Avery CW, Easterling DR, Kunkel KE, Lewis KLM, Maycock TK, Stewart BC (eds). Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, vol II. Washington DC: US Global Change Research Program. p 572–603. Available online https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/downloads/NCA4_Ch15_Tribes-and-Indigeno.... Accessed 3 Mar 2020

Ferguson DB, Alvord C, Crimmins M, Redsteer HM, Hayes M, McNutt C, Pulwarty R,Svoboda M. 2011. Drought preparedness for tribes in the Four Corners region [report from April 8-9 2010 workshop]. Tucson AZ: University of Arizona, The Institute of the Environment, Climate Assessment for the Southwest. 42 p. Available online https://www.drought.gov/drought/sites/drought.gov.drought/files/media/re.... Accessed 13 May 2020.

Ford JD. 2012. Indigenous health and climate change. American Journal of Public Health 102(7):1260-6.

Forman F, Solomon G, Morello-Frosch R, Pezzoli K. 2016. Chapter 8—Bending the curve and closing the gap: climate justice and public health [online special collections report]. Oakland CA: University of California Press. Collabra 2(1):22. http://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.67.

Gamble J, Balbus J, Berger M, Bouye K, Campbell V, Chief K, Conlon K, Crimmins A, Flanagan B, Gonzalez-Maddux C, Hallisey E, Hutchins S, Jantarasami L, Khoury S, Kiefer M, Kolling J, Lynn K, Manangan A, McDonald M, Morello-Frosch R, Hiza M, Sheffield P, Thigpen Tart K, Watson J, Whyte KP, Wolkin AF. 2016. Populations of concern [chapter 9]. In: Crimmins A, Balbus J, Gamble JL, Beard CB, Bell JE, Dodgen D, Eisen RJ, Fann N, Hawkins MD, Herring SC, Jantarasami L, Mills DM, Saha S, Sarofim MC, Trtanj J, Ziska L (eds). The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: a scientific assessment. Washington DC: US Global Change Research Program. p 247-86. Available online https://health2016.globalchange.gov/high/ClimateHealth2016_09_Population.... Accessed 13 May 2020.

Givens M, Jovaag A, Roubal A. 2019. Montana: 2019 county health rankings report. Madison WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. 16 p. Available online https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/media/document/.... Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Great Falls Tribune. 2018 (Feb 21). Critical human needs rise as Blackfeet endure unrelenting winter storms. Available online https://www.greatfallstribune.com/story/news/2018/02/21/critical-human-needs-rise-blackfeet-endure-unrelenting-winter-storms/359300002/. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Greene KM, Rossheim ME, Murphy ST. [undated]. Drinking and driving in the Big Sky state: key insights from young adults [report]. Bozeman MT: Montana State University, Center for American Indian and Rural Health Equity. 8 p. Available online http://www.montana.edu/cairhe/other-investigators/greene/Drinking%20and%.... Accessed 9 May 2020.

Haggerty JH, Haggerty MN, Roemer K, Rose J. 2018. Planning for the local impacts of coal facility closure: emerging strategies in the US West. Resources Policy 57:69-80.

Havre Daily News. 2020 (May 20). Impact and cost of St. Mary Diversion failure still being assessed [article]. Available online https://www.havredailynews.com/story/2020/05/20/local/impact-and-cost-of.... Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

Headwaters Economics. 2018 (Jun). New Montana homes increase wildfire risks [online report]. Available online https://headwaterseconomics.org/wildfire/homes-risk/new-montana-homes-in.... Accessed 2 May 2020.

Headwaters Economics. 2019. Populations at risk [website]. Available online https://headwaterseconomics.org/tools/populations-at-risk/. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

HealthCareInsider. 2020 (Sep 30). Montana health insurance [webpage]. Available online https://healthcareinsider.com/montana-health-insurance-33111. Accessed 16 October 2020.

Heindel JJ, Balbus J, Birnbaum L, Brune-Drisse MN, Grandjean P, Gray K, Landrigan PJ, Sly PD, Suk W, Slechta DC, Thompson C, Hanson M. 2016. Developmental origins of health and disease: integrating environmental influences. Endocrinology 156(10):3416-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1394.

Hendryx M. 2009 (Jan). Mortality from heart, respiratory, and kidney disease in coal mining areas of Appalachia. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 82(2):243-9. doi:10.1007/s00420-008-0328-y.

[HRSA] Health Resources and Services Administration. [undated]. Health workforce: shortage designation scoring criteria [website]. Available online https://bhw.hrsa.gov/shortage-designation/hpsa-criteria. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Rosenthal S, Kotcher J, Bergquist P, Ballew M, Goldberg M, Gustafson A. 2019. Climate change in the American mind: April 2019. New Haven CT: Yale University and George Mason University, Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. 71 p. Available online https://osf.io/296be/. Accessed 13 May 2020.

Martin C, Doyle J, LaFrance J, Lefthand MJ, Young SL, Three Irons E, Eggers M. 2020. Change rippling through our waters and culture. Journal of Contemporary Water Research and Education. Forthcoming.

Martinuzzi S, Steward SI, Helmers DP, Mockrin MH, Hammer RB, Radeloff VC. 2015. The 2010 wildland-urban interface of the conterminous United States. Research Map NRS-8. Research map NRS-8. Newtown Square PA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 124 p. Available online https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/48642. Accessed 13 May 2020.

Montana Department of Agriculture. 2013. Developing Montana’s direct farm markets and supply chains: mapping their progress, setting a new course FY2010 [report]. p 28-30. Available online https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/MT%201117.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

Montana Department of Revenue. [undated]. Montana and manufactured homes [website]. Available online https://mtrevenue.gov/property/property-types/mobile-manufactured-homes/. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Montana Food Bank Network. [undated]. Hunger in Montana [website]. Available online https://mfbn.org/hunger-in-montana/. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

[MOPI] Montana Office of Public Instruction. 2019. 2019 Montana youth risk behavior survey: high school results [internal report]. Helena MT: Montana Office of Public Instruction. p 29. Accessible online http://opi.mt.gov/Portals/182/Page%20Files/YRBS/2019YRBS/2019_MT_YRBS_Fu.... Accessed 27 May 2019.

Moyce S, Nealy E. 2019. Montana’s hot jobs: heat-related illness in the occupational setting. Presented at: Montana Environmental Health Association/Montana Public Health Association Annual Conference and Meeting. 17-18 Sep 1919. Bozeman MT.

[MPHIS] Montana Public Health Information System . [undated]. Query results for Montana birth data, years 1999 to 2018—average number of prenatal visits [website]. Available online http://ibis.mt.gov/query/result/birth/BirthBirthCnty/AvgPNCVisit.html. Accessed 5 May 2020.

[MORHAHEC] Montana Office of Rural Health and Area Health Education. 2017. Addressing health needs in rural Montana: an aggregate summary of community health needs assessments and implementation plans of Montana critical access and rural hospitals 2015-2017 [internal report]. Available online via http://healthinfo.montana.edu/morh/chsd/about.html (navigate to “View addressing health needs report”). Accessed 15 Apr 2020.

[MTDEQ] Montana Department of Environmental Quality. [undated]. Drinking water rules and monitoring [website]. Available online https://deq.mt.gov/Water/DrinkingWater/Monitoring. Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

[MTDPHHSa] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. [undated]. Montana chronic disease plan. Helena MT: MTDPHHS. 51 p. Available online https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/publichealth/documents/Diabetes/Overall/.... Accessed 24 August 2020.

[MTDPHHSb] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. [undated]. Priority area 3: motor vehicle crashes [website]. Available online https://dphhs.mt.gov/ahealthiermontana/mvcs. Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[MTDPHHS] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. 2016. 2016 Montana behavioral risk factor surveillance system annual report [report]. Helena MT: Montana DPHHS, Office of Epidemiology and Scientific Support. 46 p. Available online https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/publichealth/documents/BRFSS/Annual%20Reports/BRFSS_Annual_Report_2016.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[MTDPHHS] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. 2017 (Oct). Trends in infant mortality, Montana 2006-2015 [report]. Helena MT: Montana DPHHS, Office of Epidemiology and Scientific Support. 4 p. https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/publichealth/documents/Epidemiology/VSU/VSU_InfantMortality_2006_2017.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[MTDPHHS] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. 2019a (Feb). Montana state health assessment 2017—a report on the health of Montanans. Available online: https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/ahealthiermontana/2017SHAFinal.pdf. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

[MTDPHHS] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. 2019b. Suicide prevention strategic plan 2019 [report]. p 2. Available online https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/suicideprevention/StateSuicidePlan2019.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

[MTDPHHS] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. 2020a (Jan). Montana state health improvement plan 2109-2023 [internal report]. 35 p. Available online https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/ahealthiermontana/2019SHIPFinal.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[MTDPHHS] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. 2020b. Governor Bullock announces plan to invest $80 million in community mental health services over five years [press release]. Available online https://dphhs.mt.gov/aboutus/news/2020/investmentalhealthservices. Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

[MTHCF] Montana Healthcare Foundation. [undated]. Improving the health and well-being and reducing disparities in health and life expectancy among American Indian people in Montana [website]. Available online https://mthcf.org/focus-areas/american-indian-health-2/health-disparities/. Accessed 1 Mar 2020.

[MTOPI] Montana Office of Public Instruction. 2019. Montana youth risk behavior survey. Available online https://opi.mt.gov/Portals/182/Page%20Files/YRBS/2019YRBS/2019_MT_YRBS_F.... Accessed 14 May 2020.

[MTPHIS] Montana Public Health Information System. [undated]. MT-IBIS [health] indictor reports [website]. Available online http://ibis.mt.gov/indicator/view/InjuryMVCDeath.Year.MT_US.html. Accessed 13 May 2020.

[NASS] National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2019 (April). Montana agricultural facts 2018. Helena MT: NASS. 4 p. Available online https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Montana/Publications/Speci.... Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

NBC News. 2018 (Dec 24). Climate grief: the growing emotional toll of climate change [article]. Available online https://www.nbcnews.com/health/mental-health/climate-grief-growing-emoti.... Accessed 4 May 2020.

[NCCDPHP] National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2019. About chronic diseases [website]. Available online https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

[NEAA] Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance. 2012. 2011 Residential building stock assessment: single-family characteristics and energy use. A report to NEAA from Ecotope Inc, Seattle WA. 231 p. Available online https://neea.org/img/documents/residential-building-stock-assessment-sin.... Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

[NEAA] Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance. 2014. Montana single-family homes—state summary statistics [internal report]. 21 p. Available online https://neea.org/img/documents/montana-state-report-final.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

[NPR] National Public Radio. 2019 (Feb 12). Lung function decline continued one year after Rice Ridge Fire, research finds [report]. Available online https://www.mtpr.org/post/lung-function-decline-continued-one-year-after.... Accessed 4 May 2020.

Ojima D, Steiner J, McNeeley S, Cozetto K, Childress A. 2013. Great Plains Regional Climate Assessment Technical Report, National Climate Assessment 2013. Washington DC: Island Press. 224 p.

[OMB] Office of Management and Budget. 2010. 2010 standards for delineating metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. Federal Register/ Vol. 75, No. 123 / Monday, June 28, 2010 / Notices. p 37246. Available online https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/fedr.... Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Orr A, Migliaccio CAL, Buford M, Ballou S, Migliaccio CT. 2020. Sustained effects on lung function in community members following exposure to hazardous PM2.5 levels from wildfire smoke. Toxics 8(53):1-14. doi:10.3390/toxics8030053.

Peterson W, Bond N, Robert M. 2015. The warm blob—conditions in the northeastern Pacific Ocean [article]. PICES Press 23(1):36-8. Available online https://www.pices.int/publications/pices_press/volume23/PPJanuary2015.pdf. Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Prasad S, Sung B, Aggarwal BB. 2013. Age-associated chronic diseases require age-old medicine: role of chronic inflammation. Preventative Medicine 54(1):S29-37. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.011.

Ravanelli N, Casasola W, English T, Edwards K M, Jay O. 2019. Heat stress and fetal risk. Environmental limits for exercise and passive heat stress during pregnancy: a systematic review with best evidence synthesis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 53(13):799-805.

Redsteer MH, Kelley KB, Francis H, Block D. 2011. Disaster risk assessment case study: recent drought on the Navajo Nation, southwestern United States. Contributing paper for the Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Reston VA: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and US Geological Survey. 19 p. Available online https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260710023_Disaster_Risk_Assessm.... Accessed 14 May 2020.

Reid CE, Brauer M, Johnston FH, Jerrett M, Balmes JR, Elliott CT. 2016. Critical review of health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Environmental Health Perspectives 124:1334-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1409277

[RHIhubb] Rural Health Information Hub. 2018. Montana [website]. Available online https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/states/montana. Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

[RHIhub] Rural Health Information Hub. 2020. Health and healthcare in frontier areas [website]. Available online https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/frontier. Accessed 14 Apr 2020.

Siddika N, Balogun HA, Amegah AK, Jaakkola JJK. 2016. Prenatal ambient air pollution exposure and the risk of stillbirth: systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 73(9):573-81. doi:10.1136/oemed-2015-103086.

Sommers BD, Gawande AA, Baicker K. 2017. Health insurance coverage and health—what the recent evidence tells us. New England Journal of Medicine 377(6):586-93. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb1706645.

Smith E, Ahmed S, Dupuis V, Running Crane M, Eggers M, Pierre M, Flagg K, Byker Shanks C. 2019. Contribution of wild foods to diet, food security, and cultural values amidst climate change. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 9(B):191-214. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2019.09B.011.

Spokesman-Review. 2018 (Feb 27). Relentless winter brings state of emergency to Montana reservations [article]. Available online https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2018/feb/27/relentless-winter-brings-state-of-emergency-to-mon/). Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Sun X, Luo X, Zhao C, Chung Ng RW, Lim CED, Zhang B, Liu T. 2015. The association between fine particulate matter exposure during pregnancy and preterm birth: a meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 15:300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0738-2.

Time. 2019 (Nov 21). Terrified of climate change? You might have eco-anxiety [article]. Available online https://time.com/5735388/climate-change-eco-anxiety/. Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

US Census Bureau. [undated]. 2017 ACS 1-year estimates [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/tabl.... Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2010. 2010 census: population density data [website data source. Available online https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2010/dec/density-data-text.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2018a. Delineation files [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/time-series/demo/metr.... Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2018b. Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas population totals: 2010-2018 [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-m.... Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2018c. Quick facts Montana [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MT/RHI325218#qf-headnote-a. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2018d. County population totals and components of change: 2010-2018 [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-countie.... Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2018e. US Census American community survey 2013-2017 5-year data release [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2018/acs-5year.html. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

US Census Bureau. 2019. State population by characteristics: 2010-2019 [website data source]. Available online https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-state-d... gov. Accessed 29 Feb 2020.

US Commission on Civil Rights. 2003. A quiet crisis: federal funding and unmet needs in Indian Country. Washington DC: US Commission on Civil Rights. 136 p. Available online https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/na0703/na0204.pdf. Accessed 24 August 2020.

US Commission on Civil Rights. 2018. Broken promises: continuing federal funding shortfall for Native Americans. Washington DC: US Commission on Civil Rights. 314 p. Available online https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2018/12-20-Broken-Promises.pdf. Accessed 24 August 2020.

[USDA] US Department of Agriculture. [undated]. Federal-state marketing improvement program [web site]. Available online https://www.ams.usda.gov/services/grants/fsmip. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

[USEPA] US Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. Climate change and the health of people with existing medical conditions [report]. US EPA report 430-F-16-059. 2 p. Available online https://www.cmu.edu/steinbrenner/EPA%20Factsheets/existing-conditions-he.... Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

[USGCRP] US Global Change Research Program. 2016. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: a scientific assessment. Crimmins A, Balbus J, Gamble JL, Beard CB, Bell JE, Dodgen D, Eisen RJ, Fann N, Hawkins MD, Herring SC, Jantarasami L, Mills DM, Saha S, Sarofim MC, Trtanj J, Ziska L (eds). Washington DC: US Global Change Research Program. 332 p. Available online https://health2016.globalchange.gov/low/ClimateHealth2016_FullReport_sma.... Accessed 14 May 2020.

Whitlock C, Cross W, Maxwell B, Silverman N, Wade AA. 2017. 2017 Montana Climate Assessment. Bozeman and Missoula MT: Montana State University and University of Montana, Montana Institute on Ecosystems. 318 p. Available online http://montanaclimate.org. Accessed 9 May 2020. doi:10.15788/m2ww82.

[YPCCC] Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. 2019. Yale climate opinion maps 2019 [website]. Available online https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/. Accessed 30 Apr 2020.