05. CLIMATE HEALTH ACTIONS

Margaret Eggers, Alexandra Adams, and Susan Higgins, with contributing authors Robert Byron, Amy Cilimburg, Angelina Gonzalez-Aller, Paul Lachapelle, Miranda Margetts, Jennifer Robohm, and Nick Silverman,

Planning, preparation, and collaboration across all sectors, both at the state and community levels, are critical to reducing the broad impacts of climate change on public health. This section describes planning guides, action strategies, and information sources[1] for 1) communities, 2) healthcare practitioners and institutions, and 3) individuals, organized for each sector by the key health issues described in Section 3. These tools will help communities and individuals access local climate and health data, assess the greatest threats to local well-being, prioritize goals and objectives, and prepare accordingly.

Planning, preparation, and collaboration across all sectors, both at the state and community levels, are critical to reducing the broad impacts of climate change on public health.

While the risks and outcomes of climate change may seem beyond anyone’s direct control, many manageable actions exist for protecting our communities, our families, and ourselves. The goal of this section is to provide information that helps Montanans maintain optimal health in the face of climate change.

Tackling problems of climate-induced environmental issues—e.g., warmer temperatures, increased forest disease and fire, or changing water quality and availability—often involves discussions of mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation is the work to reduce or stabilize the climate changes already taking place. Adaptation involves efforts to adjust to life in a changing climate. Mitigation and adaptation efforts also apply to tackling climate-induced human health issues. Citizen involvement in climate change adaptation and mitigation planning and action is already underway in some Montana counties, and several case studies are provided below.

Mitigation is the work to reduce or stabilize the climate changes already taking place. Adaptation involves efforts to adjust to life in a changing climate.

For some, tackling climate change may seem like too great a challenge, but even small efforts to improve health, well-being, and resilience make a difference for climate change mitigation and adaptation. It is time to work on building relationships, developing collaborations, and understanding who around you are most vulnerable to climate change, and who are best positioned to provide support.

Community Actions: Teaming Up for Success

A fall 2019 statewide survey of 222 Montana public-health and environmental-health professionals asked their concern regarding climate change. Almost three-fourths of respondents said that health departments should be preparing to deal with the public and environmental health effects of climate change, although less than 30% of the departments were currently doing so (Byron 2019; see sidebar Montanans and Climate Concerns in Section 2). Almost all respondents indicated that multiple entities should work together in this effort.

Top Actions for Communities

Join or create a broad community coalition, optimally including your local health department, and start working together across sectors to create and implement a community resilience plan that includes climate change mitigation and adaptation and.

-

Identify human, organizational, financial, and other resources for conducting your work.

-

Assess local climate change concerns such as extreme heat, poor air quality, drought/floods, food and water insecurity, vector borne diseases, and more.

-

Gather the local/county epidemiological (health) and climate data needed for your work.

-

Recognize that public health and economic well-being are inseparable—planning for climate change impacts will protect both.

-

Assure that more vulnerable groups, including those with mental health concerns, are incorporated into all planning efforts.

Building resilience to climate change impacts on public health requires collaboration across all sectors: state, tribal, county, and municipal governments. It includes elected leadership; emergency management teams; public healthcare systems and practitioners; and local organizations, businesses, and community members (UNDRR and WHO 2020). A wealth of online materials is available to help build our resilience to climate change impacts. Developed by federal agencies and professional and non-profit organizations, these materials provide many examples from successful communities. In addition, many useful tools can be found in the Institute on Ecosystems’ Climate Smart Montana Program[2] and in the subsections that follow. Our list of top actions for communities is presented below.

Steps to create a community climate action plan

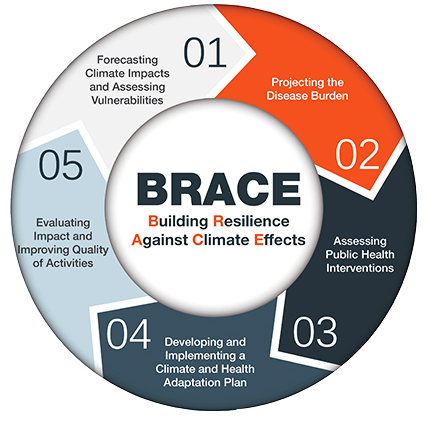

The Centers for Disease Control’s Climate and Health’s Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) plan provides an excellent guide for creating a community climate action plan. This plan describes a five-step program to assist health officials and communities in preparing for health effects resulting from, or worsened by, climate change (Figure 5-1) (CDC 2019).

Initiating the BRACE (or other) planning framework requires broad community engagement and one or more government agencies, citizen groups, or organizations committed to leading the effort. Join with others in your community who are already addressing or are beginning to address the impacts of climate change on local health. As a team, carefully consider the support of your citizens and leaders. Assess your community’s capacity to develop a health and climate action plan. Is the CDC’s BRACE framework, or some other process, best suited to address your community’s capacity and needs?

It is possible, and perhaps likely, that a community’s first step will be to implement a well-thought-out engagement and education campaign or initiate some actions that will excite and galvanize a multi-sector coalition. As the National League of Cities advises in its multi-faceted guide to local actions to address climate change, “Start with people, stay with people: build an inclusive, broad public engagement program with local partners to grow public support and political will for climate action” (NLCI undated). Including the public in initial planning leads to more public participation in plan implementation, and better understanding of community vulnerabilities (van Aalst et. al 2008; IPCC 2014; Di Matteo et al 2018).

As the National League of Cities advises…, “Start with people, stay with people: build an inclusive, broad public engagement program with local partners to grow public support and political will for climate action.”

Implementing a BRACE plan in Montana ideally requires access to county-level climate and air quality data, updated climate projections, and current and projected disease burden related to climate, as well as a better understanding of climate-vulnerable populations. With these data and the BRACE framework, state, tribal, and local leaders can collaborate across sectors more effectively to prepare for, manage, and reduce the health and economic impacts of climate changes (UNDDR 2020; UNDDR and WHO 2020). Data availability and access challenges—some of which are detailed below—exist in every community but should not impede planning and taking action. Data gaps and missing analyses that are consistently identified can become work mandates for state agencies and academic institutions.

The next step in creating a climate action plan is to assess sensitivity, exposure, and risk for your community. This assessment will form the basis for your community’s plan, and outline how it will address human health issues that result from climate change. Include local leaders, health professionals, a diverse stakeholder group representing your community, and people experienced in creating climate change plans. Explore the following questions:

- What are the major climate- and health-related risks facing your community now and expected in the coming decades? The impacts of climate change on health may also vary widely among community members (Islam and Winkel 2017; National Geographic 2019). Develop a climate action plan that is equitable, feasible, and tailored to community demographics (e.g., age and income distributions), exposures (e.g., climate components like increasing temperatures), and risks (e.g., the likelihood that exposure events like major wildfires or flooding will occur).

- Carefully consider the needs of each community’s unique vulnerable populations, as described in Section 4. Who are the most vulnerable? Why? What can be done to increase their resilience?

- Are any stakeholder groups underrepresented on your team? If so, how can you engage them?

- Beyond applying to the CDC’s Climate-Ready States and Cities Initiative[4] for funding, what financial resources are available for this process and for outside facilitation to help guide discussions and actions?

- What kind of community outreach will your team need to implement before, during, and after development of your climate action plan?

- Could first-step targeted activities be initiated in your community before conducting a full climate and health assessment plan? If so, what steps? Getting started is one way to build support for further action, plus it can help develop climate and health literacy.

With persistence and patience, capable facilitation, and access to health- and climate-science expertise, your community can assess its health vulnerabilities to climate change, identify the most suitable and highest priority interventions, and then create and continuously improve your community climate action plan. That plan will describe mitigation or adaptation actions that fit your local conditions. For example, the Blackfeet Tribe, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and the community of Missoula have actively responded to climate-related changes faced by their people and landscapes (see sidebars).

Community Climate Action Planning for Health Resilience—Tips from Missoula

Amy Cilimburg, Executive Director of Climate Smart Missoula

More wildfire smoke combined with extreme heat is a challenge to physical and mental health—what can we possibly do? That was a question our newly formed non-profit, Climate Smart Missoula, asked a few years back as we recognized Missoulians were not prepared to “weather the changing weather.” Via our Summer Smart program, we started working on a handful of initiatives, from planting shade trees to donating indoor high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters to homebound seniors. Because we were already working with our City-County Health Department, in 2017, when hazardous smoke filled our valley, we were able to rapidly grow this program, providing HEPA filters—and thus clean indoor air—to those most at risk, from babies to people with asthma to the elderly.

This early effort helped us learn that although it may be difficult to address the intersection of health and climate change, it can be done. And there’s more to do!

Our Summer Smart efforts gave us the confidence and motivation to broaden this work. We are now partnering with Missoula County and the City to craft and implement Missoula’s first-ever resiliency plan: Climate Ready Missoulaa. We first partnered with scientists to understand climate projections and then, given these, worked with hundreds of county residents to identify who and what is most at risk and what adaptation goals and strategies would best address these risks. We highly recommend the Climate Ready Communities guideb or other similar (and free) planning resources available to help any Montana community get started.

By bringing people together to understand how we can best look ahead to the challenges coming our way and “bounce forward,” we can build social equity and strengthen a can-do attitude in the face of change. And community members will no doubt be healthier as a result of these efforts.

A few things we’ve learned along the way:

- Partner with community health professionals—they are trusted community members.

- Initiate conversations about who is most at risk in your area.

- Consider starting with a focused initiative, then expand as capacity and buy-in grows.

- Connect with neighboring communities when and where you can.

- Take care of your own personal health and go forth armed with compassion and hope.

---

a https://www.climatereadymissoula.org/

b https://climatereadycommunities.org/learn-more/about-guidebook/

Stories of Climate Change, Health, and Indigenous Ways

Blackfeet Nation

Gerald Wagner and Termaine Edmo, Blackfeet Environmental Office

In 2018, Blackfeet Nation released a climate adaptation plan that works to protect our diverse ecosystems from the impacts of a rapidly changing climate. Underlying this plan is the Blackfeet understanding that people and nature are one, and that people can only be healthy if we ensure the health of the environment we depend on. Blackfeet Nation borders Glacier National Park to the east and Canada to the north. The Blackfeet Nation is not only our home, it's our place of origin. From the soil we walk on, to the water and land we protect, the Amskapii Pikunii people have worked hard to preserve our language, customs, traditions, and practices throughout the 10,000 years we have called this region home. We understand deeply that what happens to the Earth happens to us, and that we protect ourselves by honoring our traditional principles and values of stewardship.

Climate change threatens all we hold sacred, and the impacts of a changing climate are visible everywhere. For example, more extreme weather events are starting to disrupt power and water supplies, communication systems, and transportation, making it difficult to maintain critical services. During winter storm emergencies, people have become stranded in their homes with insufficient food or medicine, jeopardizing their health and well-being. Similarly, more intense flooding can negatively impact services.

In 2019 alone, we experienced several winter storm emergencies and a flood disaster. During such events our communities demonstrate exceptional resilience, compassion, and creativity. Neighbors help each other free vehicles from mud or snow, we drive miles out of our way to check on Elders, and we continue to work on ways to be better prepared for the next emergency.

Our climate adaptation plana works to protect the health and well-being of our people. We want our people to understand the connection between climate change and health, so our adaptation plan is the foundation from which we iikakimaat (try hard) to care for the environment and thereby our people, and our ways of life.

---

a blackfeetclimatechange.com

Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) of the Flathead Indian Reservation

Mike Durglo, Jr., Environmental Director, CSKT Natural Resources

The Flathead Indian Reservation is home to approximately 28,000 people, of which about 9000 identify as Native American. CSKT has approximately 6800 enrolled tribal members, 4000 of whom live on the reservation. On the Flathead Indian Reservation, climate change threatens our treasured landscapes, our people, and the traditional customs and practices that sustain our way of life. Climate change is the result of the worldwide establishment of a way of life that is fundamentally at odds with the traditional ways of tribal people here. This establishment, and its disregard for the environment, pose serious risks to the S’elish, Qlispe, and Ktunaxa peoplesb that call the reservation home.

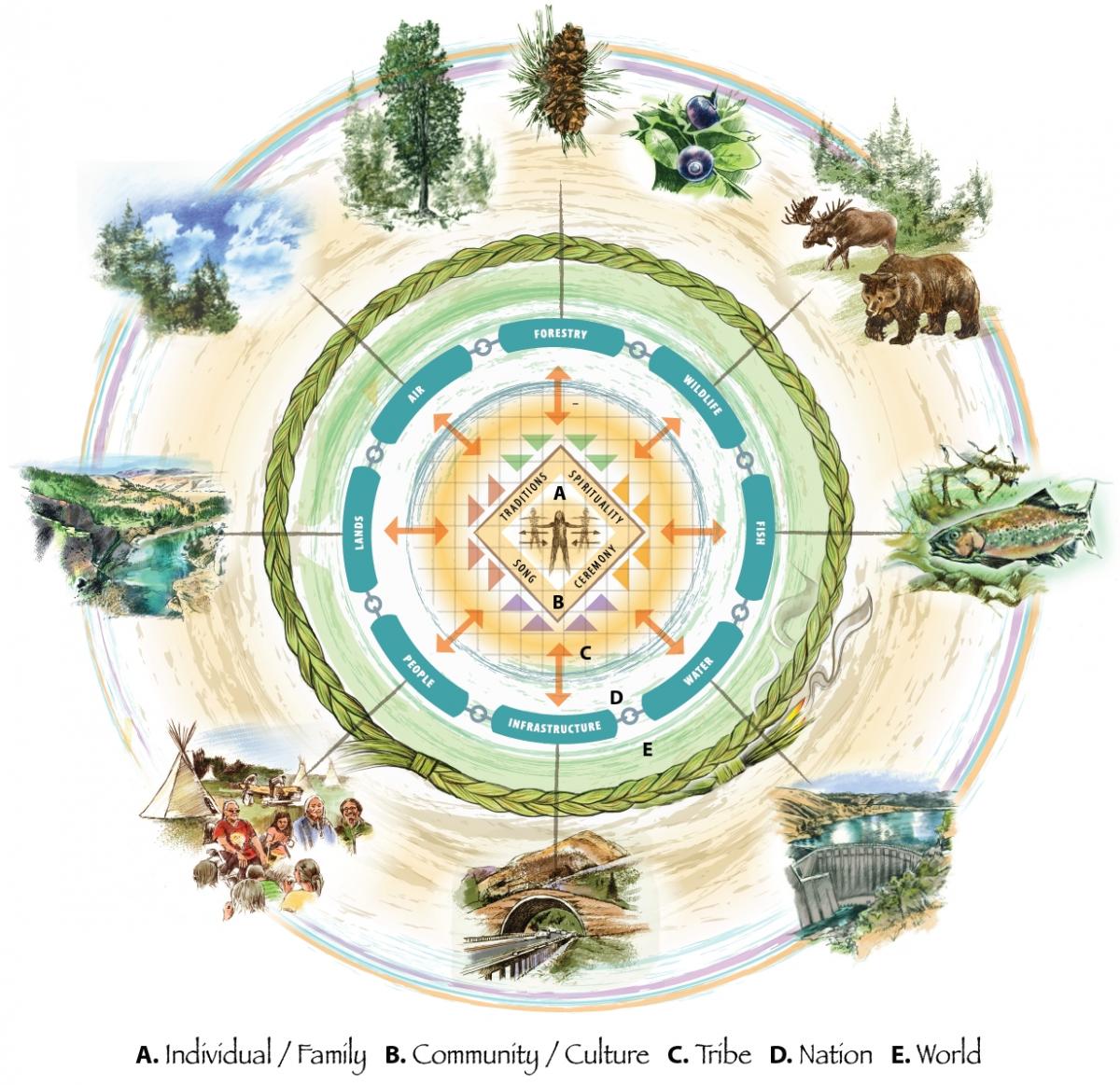

Climate change is already impacting the health and well-being of our people. Wildfires have caused hazardous air quality conditions, and extreme weather events create dangerous conditions and limit access to healthcare and other critical services. The climate crisis and the ecological changes that it brings threaten traditional customs, including our access to first foods through hunting, fishing, and gathering, and our ability to conduct ceremonies and spiritual practices. Many foods and medicinal plants grow on the reservation and aboriginal lands. As a result, climate change threatens our cultural survival, which directly affects both our physical and mental health. To address these risks, CSKT released our first Climate Change Strategic Planc in 2013 and is taking deliberate actions to address climate impacts wherever possible. Our tribal values affirm that everything is connected and that human beings have a responsibility to care for the things that were placed here, before the human beings.

As with all things, the CSKT follow the circle pathway worldview. Our Elders teach that all things are connected and that any impact or action on one resource will impact all. The diagram shown illustrates a tribal way of thinking as also expressed during our recent climate planning session. Climate-related disturbances including flood, drought, wind events, and wildfires impact our tribal resources, and will therefore impact our culture, traditions, and our foods and spirituality—without which our lifeways cannot survive. Impacts are also expected to be place-based. Impacts in the high-elevation region will be different from impacts to resources in the dry-grass and sage-steppe ecoregions of the reservation. The climate crisis requires immediate and sustained action to protect human health and well-being. For the people of CSKT, this requires protecting the ways of life that define us as a people.

---

b The Tribes which in English are called the Salish, Pend d'Oreille, and Kootenai.

c http://csktclimate.org/

We understand deeply that what happens to the Earth happens to us, and that we protect ourselves by honoring our traditional principles and values of stewardship.

* * * *

Climate change is the result of the worldwide establishment of a way of life that is fundamentally at odds with the traditional ways of tribal people here. This establishment, and its disregard for the environment, poses serious risks….

Act on climate change not only for public health, but also economic well-being

As we are learning during the current COVID-19 pandemic, public health and economic well-being are inseparable. The same concept applies to climate-driven increases in wildfire, flood, and drought, which not only directly affect our health and our economy, but are also starting to influence state and local government credit ratings. Broad collaboration and planning will reduce the intertwined health and economic impacts of climate change.

Climate surprises—such as heat waves, drought, flooding, or other disasters—can trigger an exodus of residents, resulting in declining tax revenue, or bring a flood of new immigrants to the state from regions that are experiencing worse conditions. Damage to municipal infrastructure from severe storms, floods, wildfires, or other disasters can incur major expenses for communities. For instance, a major wildfire may result in runoff water of such poor quality that a community's current water plant can no longer adequately treat it. Such occurrences add to the risks that rating agencies assess. As a result, they might lower a government’s credit rating and ultimately increase its cost of borrowing money via bonds (Fitch Ratings 2018; Pew 2019; DeFries et al. 2019; Janney Investment Strategy Group 2019; New York Times 2019).

To better assess climate change risks, the rating agency Moody’s recently bought a controlling share of a company that specializes in climate change risk assessment. According to the New York Times, several major rating agencies, including S&P Global and Moody’s (Moody’s Investor Services 2017), have issued reports “…warning state and local governments that their exposure to climate risk could affect their credit rating. Moody’s has said that cities and counties with plans for reducing their exposure to climate risks, by updating their infrastructure for example, could see their ratings improve as a result, or at least not deteriorate” (New York Times 2019).

Moody’s Analytics: “Cities and counties with plans for reducing their exposure to climate risks, by updating their infrastructure for example, could see their credit ratings improve as a result, or at least not deteriorate.”

Communities need climate and health data for planning and action

One challenge facing Montana’s communities is that the climate and epidemiologic data necessary for planning are not currently collected for and shared with all counties in Montana. The coverage of NOAA/National Weather Service (NWS) meteorological stations is uneven in Montana, such that some parts of the state have limited direct information (NOAA-NCEIa undated). Additionally, only a small number of the meteorological stations have operated long enough to characterize long-term trends in climate variables (NOAA-NCEIb undated). Several programs seek to fill the gap. First, NOAA/NWS improves the coverage of recording sites by using participating cooperative observer information (NWSb undated) to provide a network of minimum/maximum temperatures, precipitation, snowfall, and snow depth. However, parts of Montana have relatively few of these sites and the time span of records is variable. Second, the Montana Climate Office is a partner in NOAA’s Mesonet program, set up to deploy automated weather and environmental monitoring stations at 74 sites across the state, and thus increase the spatial coverage of weather data and improve services (MCO 2020).

Further, the Montana Climate Office is working with US Army Corp of Engineers and NOAA to establish and maintain upwards of 220 additional monitoring stations across the state over the next 5-7 yr.[5] The US Army Corp of Engineers and NOAA federal funding will support better soil moisture and snowpack monitoring for flood forecasts and drought assessment. However, little funding exists for updating and analyzing historical and recent climate trends, or local climate projections. Other funding will be necessary to add air-quality monitoring sensors to these stations, as presently there are only 20 air-quality monitoring stations managed by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Although the department posts current air quality conditions online, 20 stations provide only limited coverage and historical data are not provided.[6]

MCA provides climate projections for Montana, focused on the seven NOAA climate divisions in the state (Whitlock et al. 2017; Section 2). However, projections at the climate division level are too coarse to assess climate trends for particular counties or communities. Each division covers a large area and their boundaries are not defined by physical geography. Local experience suggests this may be particularly true for changes in precipitation patterns (Doyle et al. 2013; Martin et al. 2020). The spatial resolution of climate projections will improve in future Montana climate assessments, with a scale that will be even more useful for community-level planning.

County-level epidemiologic data are also required for the CDC’s BRACE framework (CDC 2019), reviewed above. Statewide epidemiological data are collected by the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, but for a variety of reasons are not easily accessible at the county or community level. We need shared, statewide monitoring of health-facility visits related to climate change, especially county-level data about visits related to smoke, heat, or home-mold exposure; vector- or water-borne illnesses; and mental health concerns.[7] In sum, data are a critical need for climate monitoring agencies and communities—particularly for state and county public health departments and their collaborators—to address the impacts of climate change on health. To meet that need the state of Montana, in collaboration with relevant federal agencies, should:

- increase the network of meteorological stations in the state to fill in geographic gaps;

- add to the network of air quality stations monitoring for particulate matter to fill in geographic gaps;

- increase funding to the Montana Climate Office for historical and current analysis of climate and human health trends and patterns at the state, county, and community scales;

- improve the spatial resolution of climate projections to provide county-level information; and

- create a shared, statewide monitoring process of health-facility visits related to climate change, with county-level data available to communities.

Strategies and actions for communities

The remainder of this section highlights some strategies your community will want to consider in planning and preparing for health-related impacts from climate change. How you prioritize these categories will depend on your review of the data and discussions across your multi-sector collaboration. Appendix B provides a tabularized list of resources for communities, including public and environmental health agencies and organizations, to develop climate change assessments and action plans.

Heat

Two strategies communities can use to address heat-related impacts to health are to: 1) inform citizens about the dangers of overheating in extreme temperatures; and 2) provide cool or cooler spaces both inside and outside. Examples include:

- Encourage employers to improve the workplace environment and policies to reduce heat exposure. During extremely hot weather employers should, for example, provide outdoor workers ready access to shade, drinking water, and restroom facilities, plus allow break time for workers to cool off.

- Inform those working, playing, or otherwise spending extended time outdoors about the importance of resting, hydrating, and seeking shade to avoid potentially life threatening, heat-related health issues.

- Designate (or create) a cooling facility for your community or workplace where people can go during a heat emergency. Such a facility might be an air-conditioned school or community center, or a deeply shaded park, perhaps near a community swimming pool, lake, or river.

- Ensure vulnerable populations (see Section 4) understand heat-related health issues and have a plan for staying cool. For example, develop programs to ensure access to cool community spaces. Likewise, ensure that those most vulnerable to extreme heat have window fans or air conditioners.

- Create incentives and programs to address the rising urban heat-island effect (USEPAd undated). Examples include substituting lighter colored materials in place of black asphalt and tar on roads and driveways, and encouraging more environmentally friendly building practices, including cool roofs, constructed with light colors and heat-reflecting materials.

- Create incentives, programs, and/or campaigns to plant and care for trees and other vegetation to create shade (USEPAe undated).

Air quality

While it might be possible to mitigate some of the health effects of wildfire and smoke through forest management practices, local communities do not generally carry out such efforts. However, every Montana community can focus on adaptation strategies for dealing with wildfire by increasing their community’s fire resilience and, during wildfire season, improving air quality indoors and outside.

Actions your community can take include:

- Implement sustainable construction and encourage new housing in more sustainable and fire-safe areas (Zakaria 2020). Learn more about building fire resilience in your community through an excellent online resource titled “The science of firescapes: achieving fire-resilient communities.”[8] The Federal Emergency Management Administration provides relevant checklists for homeowners (FEMAb undated) and communities (FEMAc undated).

- Educate homeowners about assessing fire risks to their homes, checking with their insurance company on the terms of their homeowner’s wildfire coverage, and, if needed, reducing fuels around their home.

- Develop or enhance emergency response plans for forest and grassland wildfires. Create a community database of people who would need physical assistance to evacuate if required, and determine who will help those people in such emergencies.

- Inform homeowners about options to create safe indoor air using HEPA portable air cleaners, MERV 13 air filters, or HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems. See the Personal/Air Quality/Indoor Air subsection below and the Climate Smart Missoula guide to filtration systems.[9]

- Consider funding air filtration in public spaces, for example in schools, daycare centers, senior centers, municipal buildings, evacuation shelters, houses of worship, and gyms and recreational facilities. Such work is underway in Montana: the team at Climate Smart Missoula donated portable HEPA air cleaners to those who were most vulnerable.

- Encourage employers to reduce workers’ exposure to smoke and particulate matter. For example, employers could halt or limit outdoor work during periods of poor air quality, schedule (if possible) employees to work at alternative sites having less hazardous air quality, or provide protective breathing masks appropriate to the conditions.

- Encourage schools, organizations and employers to implement the federal Air Quality Flag Program.[10]

- Work with the Montana Climate Office and Department of Environmental Quality to ensure a) your community has a weather station with added sensors for particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10); and b) that the public has online access to both real-time and historical data.

Flooding and water-related illness

Flooding can impact human health in a number of ways, including by increasing exposure to vector-borne diseases.

Actions to counteract or minimize exposure include:

- Protect wetlands and restrict new development in flood-prone areas in and adjacent to your community. Wetlands retain water, slowly filtering and releasing it to surface waters, thereby improving surface water quality. Wetlands also serve as recharge areas for groundwater. Hence, wetlands protection and open space planning not only conserve habitat and local amenities, they also help protect water quality and quantity. For these reasons, identify and protect wetlands and other such groundwater recharge areas from development. If impermeable parking lots are built, design adjacent landscaping to capture and filter runoff. Note that if wetlands are destroyed by development, Montana law requires that alternate wetlands be created nearby.[11]

- One major way floods can impact health is by contaminating lakes and ponds with nutrient and sediment runoff. Excessive nutrient enrichment, termed eutrophication, can result in deaths of fish and other aquatic organisms from depleted oxygen levels (National Ocean Service, NOAA undated), and trigger hazardous algal blooms (MTDPHHS 2019). During hazardous algal blooms, algae release toxins—poisonous to humans and other animals—into the water (see Section 3, Water-Related Illnesses subsection). Best management practices such as creating vegetative buffers for water bodies and limiting excessive use of fertilizers are effective mitigation measures (USEPA 2020).

- Assess water and wastewater infrastructure needs and vulnerabilities to flooding, drought, and sediment runoff following wildfire. Does your infrastructure need upgrading to handle such events? Assure that an emergency response plan is in place in the event of an extreme weather event. The Montana Department of Environmental Quality provides a useful two-page flier[12] that includes guidelines on training, development of local emergency planning committees, core elements of an Emergency Response Plan, and compliance with the National Incident Management System.

- Ensure that emergency service providers have appropriate training, adequate supplies, and tested plans and systems ready to help those in need during flooding (and other emergency) events. Three critical items to prepare in advance are methods and logistics a) for emergency communications and outreach; b) for evacuation, including strategies, routes, and safety zones; and c) for accessing medical care. The Montana Primary Care Association[13] and two Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services programs—Ready and Safe[14] and EMS and Trauma Systems[15]—are good resources to consult.

Food security

Drought and extreme weather events impact local food security (see related sidebar in Section 3), for example, when hail damages crops. But while some Montanans source their food close to home, most rely heavily on food produced long distances away and trucked to grocery stores. Climate change in other parts of the world can impact our food security. Crop destruction or failure and transportation interruption—potential outcomes from climate “surprises” (see Section 2) or pandemics—may result in pricing increases or interruptions to Montana’s food supply. A vibrant local food system can build resilience in the face of such challenges, as well as support local economies (State of Montana 2020).

Climate change in other parts of the world can impact our food security. …. [Thus] encourage personal, small-scale agriculture, local farmers’ markets, and farm-share programs to support and diversify local food supply and empower individuals with the knowledge and skills to grow their own food.

A few examples of community actions that can help protect food security in the face of climate change are:

- Incorporate the complexities of food security into community climate action plans. Identify those who most rely on food from outside sources, with particular attention to vulnerable people.

- Develop forums to discuss how much and what kinds of foods can be stored for emergencies. Information on types and amounts of foods, as well as sanitation, cooking without power, and more can be found in the Federal Emergency Management Act[16] and Ready.gov[17].

- Encourage personal, small-scale agriculture, local farmers’ markets, and farm-share programs to support and diversify local food supply and empower individuals with the knowledge and skills to grow their own food.

- Tap resources offered by County Extension and Natural Resources Conservation Service offices to understand sustainable practices, irrigation efficiencies, and integrated pest management.

- Enhance and incentivize more effective, multi-stakeholder approaches to drought response planning through local watershed groups and public works departments.

Vector-borne and zoonotic diseases

Paying attention to outbreaks of vector-borne, zoonotic, and other infectious diseases belongs on a community’s planning radar. Climate change is a key contributor to the emergence of these diseases (see Section 3), and warming temperatures promote mosquito, tick, and other arthropod reproduction and range extension. Having good drainage near homes and mosquito control programs (e.g., municipalities that spray for mosquitos) are two ways to reduce vectors at the community level. Community education on vector-borne diseases is essential (see Actions for Individuals subsection below). Medical practitioners and those involved in public health should stay current on issues of vector-borne disease epidemiology and symptoms, as provided by the Centers for Disease Control[18], the US Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service[19], and Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services[20].

Mental health

Extreme weather events, prolonged heat and smoke, and environmental and societal change all affect mental health, including increasing feelings of disconnectedness and despair. Build a plan for community well-being. Actions include:

- Plan for increased mental health impacts of climate change by working with local hospitals, clinics, health departments, schools, and faith and service organizations to build mental health services that connect across jurisdictions in your county and community.

- Inform healthcare providers and the public about the mental health impacts related to climate-induced extreme weather events, poor air quality, rising heat, flooding, drought, and more. Discuss and plan for the potential community disruption (e.g., to healthcare access and food and water availability) that can be caused by extreme events, and how that disruption can impact the mental health of individuals and communities.

- Build in-school capacity to address mental health issues in youth related to climate change. Acknowledge the anxiety some students feel around mounting climate change impacts (Burke et al. 2018), by opening discussion among teachers, students, parents, and friends. Consider also setting up mentoring programs with community members like the Child Advancement Project established by Thrive.[21]

Extreme weather events, prolonged heat and smoke, and environmental and societal change all affect mental health, including increasing feelings of disconnectedness and despair.

Strategies and Actions for Healthcare Practitioners and Institutions

Medical practitioners, clinics, and hospitals have critical roles to play in preparing for and coping with health issues resulting from climate change. All in the medical field must become fluent in the language of climate change and its health impacts, and knowledgeable of the treatment methods they will be required to apply—be those currently used methods, or new skills they can obtain.

This subsection describes strategies and actions applicable to individual practitioners and healthcare facilities. We also recognize the many online resources on the intersection of human health and climate change available for both groups. Table 5-1 provides a number of these resources, with an emphasis on information for Montana providers.

|

Table 5-1. Information sources useful for healthcare providers, be they individuals or facilities.a |

||

|

Source |

Resource description |

Website |

|---|---|---|

|

American College of Physicians (ACP) |

Climate change toolkit for physicians, including ACP position paper, educational materials, greening the healthcare sector documents and other resources |

https://www.acponline.org/advocacy/ |

|

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) |

AAP policy statement on Global Climate Change and Children’s Health |

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ |

|

Climate Psychiatry Alliance |

What psychiatrists can do about impacts of climate change on mental health, in terms of patient care, systems of care and public health advocacy. |

|

|

American Psychological Association (APA) |

APA 2017 Publication (69 p) titled, “Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications and guidance.” |

http://ecoamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2017 |

|

American Public Health Association (APHA) |

APHA’s declared mission is to “Improve the health of the public and achieve equity in health status,” including improving mental healthcare. This brief publication referenced describes immediate, gradual and indirect impacts of climate change on mental health. |

https://www.apha.org/~/media/files/pdf/ |

|

Medical Society Consortium for Climate and Health |

Group that, among many functions, advocates for climate change action based on health impacts. |

|

|

Montana Health Professionals for a Healthy Climate (MTHPHC) |

Group that, among many functions, advocates for climate change action based on health impacts. MTHPHC welcomes all health professionals and health profession students to join as members. |

|

|

American Lung Association (ALA) |

The ALA advocates for climate action and preparedness by elected officials as well as professional and public organizations. Resources on climate change impacts on air pollution and lung health, as well as ways to fight climate change. |

|

|

MyGreenDoctor |

An evidence-based practice management tool for individual practitioners, clinics, and hospitals to save money by becoming environmentally sustainable. |

|

|

Health Care Without Harm |

Works to transform healthcare worldwide. Their Climate and Health program supports the healthcare sector in reducing its carbon footprint, building climate-smart and resilient hospitals and communities, and mobilizing healthcare's ethical, economic, and political influence to advance the transition to a low-carbon future that supports healthy people living on a healthy planet. |

|

|

Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments (ANHE) |

The Mission of ANHE: Promoting healthy people and healthy environments by educating and leading the nursing profession, advancing research, incorporating evidence-based practice, and influencing policy. |

|

|

------- a Websites shown were active as of December 2020. For the latest resources and web links, go online to the Climate Change and Human Health link at the Montana Climate Assessment website (montanaclimate.org). |

||

Practitioners

Clinicians—primary care, subspecialty, or mental health professionals—are generally trusted by their patients. Thus, healthcare practitioners trained to detect potential health impacts of climate change can not only assess and treat those health impacts, they can also inform their patients. Groups like the American College of Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Climate Psychiatry Alliance provide tools and guidelines for integrating climate- and health-related questions and discussions into routine patient visits (Table 5-1). Providers have many opportunities for productive, climate-related actions when interacting with patients, the medical community, or the community-at-large, as enumerated here.

Top Actions for Practitioners

-

Get informed about the effects of climate change on health, including mental health, so you can recognize concerns and treat your patients accordingly. Be especially vigilant during climate-related extreme-events, including droughts, floods, wildfires, and other disasters.

-

Educate your patients about the effects of climate change on health.

-

Provide educational materials about the effects of climate change on physical and mental health in your clinic and on your organizations websites.

-

Become involved with professional or public organizations advocating for climate action based on health impacts (Table 5-1).

-

Provide primary care, behavioral health, and crisis treatments that ameliorate the physical and mental health impacts of climate change (Anderson et al. 2017). The resources provided in Community Actions subsection above include checklists for health-related impacts, such as those from mold, overheating, wildfire smoke, vector-borne disease, lack of nourishing foods, and the mental health distresses from major storm and other climate-induced weather events.

-

Consider providing patient-specific information related to climate change and ways to protect yourself, both in your clinic and on your organization’s websites.

-

Be an advocate in your community providing trusted guidance and information. Become involved with professional or public organizations advocating for climate action based on health impacts (Table 5-1).

Healthcare institutions

In addition to the actions of individual practitioners, hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare facilities can make a substantial difference to their patients and communities dealing with climate-related health issues, as enumerated below.

Top Actions for Healthcare Institutions

-

Work on mitigation efforts, for example instituting energy savings programs, upgrades to HVAC systems, development or improvement of recycling programs, and more. Choose one and start!

-

Work within your organization and with community public health, community, academic leaders, and other groups to create a community plan for management of climate surprises, disasters, and pandemics.

-

Add climate health effects to electronic records for both physical and mental health.

-

Contribute to climate and health trainings for health professionals, including psychological first aid.

Here are additional actions for healthcare institutions:

Greener Healthcare Ideas

Julia Ryder BSN, RN, CEN (Founding Board Member of Montana Health Professionals for a Healthy Climatea)

According to the World Health Organization, the US healthcare system contributes 8% of our greenhouse gas emissions (WHO undated). Climate change is a threat to human health, and hospitals especially must do all they can to model best-available environmental practices.

To reduce energy usage, a healthcare facility must first know how much natural gas and fuel it uses, energy and water it consumes, and waste it produces. Once familiar with these measures, a facility can set goals to reduce them. Programs such as Practice Green Health and Health Care Without Harm help hospitals set goals and lead the way in sustainability. For example, healthcare facilities can:

-

improve local air quality by creating no idling zones on their campuses;

-

reduce toxic emissions from incinerators with clear guidelines and education for all employees regarding materials that can and cannot be processed in biohazard waste dispensers;

-

reduce laundry energy requirements by reducing the use of hot water and electricity;

-

switch to LED light bulbs (which also saves a hospital thousands of dollars); and

-

update and improve maintenance of HVAC systems that consume an enormous amount of energy.

Proper waste distribution and management must be demonstrated on every level in the hospital. The average hospital creates 29 lb (13.2 kg) of waste per patient bed per day (Eckelman and Sherman 2016). Accessibility to well-placed recycling, compost, and trash bins is important; they should be placed anywhere food is offered. To assist patients and staff, clear signage and instructions should be placed near every bin to ensure people properly segregate their waste.

Above all, if a healthcare facility wants to reduce its carbon footprint, it must build a culture of awareness by encouraging employees to turn off lights, shut down computers, utilize natural lighting, and not open materials until needed. It can reward employees who walk, bike, or carpool to work, and offer online meeting options rather than having employees drive to work for short time frames.

A hospital can also help patients become healthier by offering more vegetable-based, locally sourced meals in the cafeteria, and cooking classes on how to prepare these foods at home. Last of all, hospitals can invest in growing trees and other plants around campus. Such efforts not only improve air quality, but also provide shade and emotional support for patients and families.

----

a More information at https://www.montanahphc.org/index.php

- Improve and model sustainable practices and processes, including capturing anesthesia gases, decreasing use of disposables, shifting to renewable energy, and sourcing food locally. Tell your community that you are taking such steps, and hence helping mitigate climate change. Table 5-1 provides links to two programs—Health Care Without Harm and MyGreenDoctor.org—scoped to meet such goals (also see sidebar).

- Conduct climate adaptation and resilience planning with communities and local and state public health systems.

- Consider addressing HVAC/HEPA retrofits to maintain facility indoor air quality, particularly for hospital inpatients.

- Develop defined steps for meeting the needs of distressed communities, including not only physical ailments and distress, but also the needs of those who are mentally traumatized or have severe mental illness (Rao 2006). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a five-step plan titled Building Resilience Against Climate Effects that health officials can follow to help your community prepare for the health effects from or exacerbated by climate change (see the Community Actions subsection above for more information).

- Assess impacts on the public health, medical, and mental healthcare systems due to shifting priorities, budget cuts, and budget diversion (e.g., to fire suppression) related to climate change.

- Work with universities, insurance providers, other healthcare systems, and local and state public health agencies to acquire critical data on the mental health consequences of climate-related extreme weather events and disasters. Those data should include prevalence and severity of climate-related health conditions, hospital admissions, suicide attempts, and episodes of violence.

- Recognize that overarching psychosocial consequences of global climate change, termed climate anxiety, stem from awareness of the looming threats and current risks of climate change.

- Prepare for disruptions to mental healthcare (including availability of psychotropic medications) due to climate-related weather events and unexpected disasters that may interrupt supplies.

- Educate decision makers—be they in public health, healthcare systems, emergency response, the medical insurance industry, or local or state government—to increase understanding of where and how to invest in medical and public health infrastructure and resources.

- Implement, support, or participate in training programs for clinicians, as well as healthcare, public health, and environmental health students and professionals on the health effects of climate change. (Healthcare training is a component of healthcare systems.)

- Curriculum development.—Address the physical and mental health impacts of climate change in educational curricula for graduate and professional students in clinical health and social work training programs in Montana. Review availability of pre-professional courses and course components on a) the physical and mental health impacts of climate change; and b) community-level climate change adaptation planning. Such courses are scoped for undergraduates in healthcare, public health, and environmental health degree programs at institutions of higher education across Montana.

- Continuing education.—Provide climate health certification/training programs, continuing medical education credits, continuing education workshops, and online medical training modules for primary care, nursing, pharmacy, mental health, and public health professionals that highlight potential health and mental health impacts of climate change, and interventions to address those impacts. Examples of such efforts include the Climate Change and Health Certificate offered at the Yale School of Public Health[22], and the Climate Change and Health Training Module Series offered by the Minnesota Department of Health[23].

- Psychological First Aid.—Ensure that first responders in Montana have training to respond to the psychological impacts of climate-related weather events and disasters. Psychological First Aid is an evidence-informed modular approach to help children, adolescents, adults, and families in the immediate aftermath of disaster and terrorism.[24]

- Join local, regional and national networks of health professionals working on climate change and health.

- Encourage members to become involved in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts through Montana Health Professionals for a Healthy Climate (Table 5-1).

Strategies and Actions for Individuals

Protecting your health in a changing climate takes work, but many actions are possible for individuals to prepare for and minimize health risks associated with climate change. The recommendations that follow are broken into climate concerns similar to those addressed in Section 3 (Climate-related Health Impacts).

Top Actions for Individuals

-

Be familiar with your own (and your children’s) medical conditions and have regular checkups with a trusted healthcare professional.

-

Stay informed about climate change impacts on health.

-

Explore what you can do to become involved in community climate change and public health initiatives.

-

Become aware of local sources of mental health counseling.

-

Prepare your home now for extreme weather events. Have extras of essential medications, blankets, potable water, respiratory masks, and cleaning and food supplies on hand, and check your home insurance policies for flood and wildfire coverage.

-

Learn the signs of and remedies for heat exhaustion and heat stroke; and learn how to help yourself in extreme heat with adequate water, shade, home insulation, and salt replacements.

-

Consider installing high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters or activated carbon filters in your home or business to remove dust, pollen, and smoke particles, Be familiar with your own (and your children’s) medical conditions and have regular checkups with a trusted healthcare professional.

-

Check current air quality at http://airnow.gov, or go directly to https://fire.airnow.gov for fire, wildfire smoke, and air quality data. Historical, current, and forecast air-quality data are available from a national to regional (if not local) scale. Where monitors in Montana exist, clicking on the small circles on the map retrieves data from those particular locations.

-

Become aware of, utilize, and support local foods and renewable energy resources.

Extreme events and disaster planning

Montana is expected to experience more climate-driven weather extremes, from intense heat waves to spring flooding to late-summer drought to, potentially, more intense and more frequent storms (Whitlock et al. 2017; Section 2).

Here’s what you can do:

- Create a family emergency plan to encompass issues that are relevant to your region. Resources are available from the US Department of Homeland Security[25] and the National Safety Council[26]. Consider installing the Federal Emergency Management app on your phone.[27] Plan so that you can comfortably stay in your home during extreme events, including, for example, being snowed-in for extended periods. Have at least three days of medications, water, and food safely stored in the home. The rule of thumb is one gallon of water per person per day for three days. Make sure you have adequate blankets or sleeping bags to stay warm during low temperatures and/or power outages.

- Install a functional carbon monoxide (CO) detector in your home, especially important during cold temperatures. If you use a furnace system, check and change the furnace filter regularly.

- Seek support from a healthcare professional should you experience a traumatic, climate-driven weather event, like flooding, drought, wildfires, and severe winter storms. Such events pose serious risks to mental health, particularly if they result in displacement, or loss of property or life. They can bring increased risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal thoughts, and suicide (USGCRP 2016; Guardian 2019).

- Check with your insurance provider if your home is prone to flooding and/or mud slides, as you may need to purchase separate coverage from the National Flood Insurance Program (FEMAa undated) or elsewhere. Also, check flood risk for your home address at https://floodfactor.com/, a website created by First Street Foundation, a group of independent experts who have modelled flood risk to include climate change impacts.

Heat

MCA notes that with climate change the number of days when temperature exceeds 90oF (32oC) in Montana is increasing (Whitlock et al. 2017). The National Integrated Heat Health Information System[28] is a good resource on heat and health-related issues.

Here’s what you can do:

- Ensure that you have curtains or shades on windows during the summer, as well as adequate ventilation or air conditioning, to help keep your living space cool during high temperatures. If wildfire is not a risk where you live, consider planting trees near your home to provide shade.

- Explore retrofit options to help keep your home cooler, including white roofing and added insulation and ventilation. Resources are available to help finance retrofits, including those from Northwestern Energy[29], the Montana’s electric cooperatives[30], the Montana Department of Health and Human Services[31], the US Department of Energy[32], and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development[33].

- Know the locations of cooling centers—e.g., malls, libraries, movie theaters, civic centers, and shaded parks—in your community where you can seek shelter in extreme heat events.

- Never leave infants, children, or pets unattended in a hot car, even with the windows cracked.

- Limit your outdoor exposure on hot days, and follow these recommendations (CDC 2017; NSC 2020; NIOSH undated):

- Air conditioning, if available, is the best way to cool down.

- Stay well hydrated (drink before you get thirsty) and avoid alcohol.

- Wear loose, lightweight clothing and a hat.

- Replace water or salt lost from sweating by drinking fruit juices or sports drinks.

- Avoid spending time outdoors during the hottest part of the day (11 AM to 3 PM).

- Wear sunscreen; sunburn affects the body's ability to cool itself.

- Pace yourself when you work, run, or otherwise exert yourself. Take breaks to rest and cool down.

- Avoid losing too much water and salt, typically from excessive sweating, which can lead to heat exhaustion, rhabdomyolysis (breakdown and death of muscles), health syncope (fainting), heat cramps, heat rash, or life-threatening heat stroke. Learn the signs of these conditions[34] and pay attention to your own and your colleagues’ condition in hot weather.

Air quality

Climate change can affect respiratory health through increased air pollution, including wildfire smoke and longer dust and pollen seasons (see Section 3). People with pollen sensitivities may experience more severe reactions, and those with respiratory conditions, such as asthma, may be especially at risk of their symptoms intensifying (e.g., coughing, shortness of breath) (Wellbery and Sarfaty 2017).

Here’s what you can do:

Outdoor air quality

- Learn more about health risks from wildfire smoke, as well as how to reduce those risks, on the Montana Wildfire Smoke website (montanawildfiresmoke.org). See also the Centers for Disease Control’s website on protecting yourself from wildfire smoke.[35]

- Check current air quality anywhere in the country, including Montana, at http://airnow.gov. According to the airnow.gov website, “The US Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Park Service, tribal, state, and local agencies developed the AirNow system to provide the public with easy access to national air quality information.” The website color coding system, from green to dark red, shows what level of health risk exists for your region. An Airnow app is available for iOS and Android mobile devices.

- Check current air quality anywhere in the country, including Montana, at http://airnow.gov. The website was created by the US Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Park Service, and tribal, state, and local agencies to provide the public understandable, easy-to-access national air quality information. The website color coding system, from green to dark red, shows what level of health risk exists for your region. An Airnow app is available for iOS and Android mobile devices.

- Montana data on particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution is available at https://www.montanawildfiresmoke.org/todays-air.html, which also provides information on how to estimate air quality based on visibility. On a clear day, establish pre-determined landmarks visible at various distances (1, 2, 5, 9, 13 and >13 miles), standing with your back to the sun. When there is smoke in the air, check for the visibility of these landmarks again. The more limited your visibility, the greater the PM2.5 levels. Consult http://deq.mt.gov/Air/SF/breakpointsrevised to translate your visibility numbers into health risks.

- Remove trees, dead brush, or other flammable materials near your home’s exterior to protect against wildfire. The National Fire Protection Agency provides a set of guidelines for protecting your home[36], plus check with your local fire department for advice applicable to your local conditions.

- As mentioned previously, check your home insurance to understand—and establish or increase if needed—your wildfire coverage.

- Carefully monitor the status of wildfires in your region. If you live in a high-fire-risk area, have an evacuation plan and be prepared to leave your home quickly.

- Avoid extended periods outside when smoke is present. Wildfire smoke creates a fine particulate matter that cannot be filtered by dust masks or bandanas. Those with respiratory conditions and children under 18 are especially vulnerable to wildfire smoke. Those over 65 yr are at increased risk of heart attack or stroke (Wettstein et al. 2018) (also see Section 3).

- Do not hold or participate in outdoor activities, especially rigorous outdoor activities like running and other sports, when wildfire smoke or haze is visible. Check with your local health department for air quality advisories for outdoor sports events. Ask your children’s schools if they receive air quality advisories and if so, if they abide by them. (Health departments can only provide advice; schools decide whether to cancel sports events).

- Monitor pollen conditions, develop a treatment plan with your doctor, and have the necessary medications on hand. The ragweed pollen season in central North America is increasing in length as temperatures increase (Ziska et al. 2011). Periods of drought may also increase irritants, so limit your time outside during times of high pollen and/or dust. Consider downloading one of the many phone apps—some free—for displaying and forecasting pollen counts and other allergens.

Indoor air quality

- Protect air quality inside your home by using air filters and keeping doors and windows closed when outdoor air quality is poor. If you have central air, improve your indoor air quality by upgrading your system’s air filter. Filters are rated using the Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV), ranging from 1-20. The higher the MERV, the more effective the filter at removing small particles (USEPAa undated). The minimum MERV rating for removing the fine particulate in smoke is MERV 13. The more times air passes through the MERV 13 filter, the cleaner the air becomes. Note that a higher-rated MERV filter will likely need to be changed more frequently due to the amount of material it accumulates.

Not all central air systems can handle the pressure drop associated with higher MERV filters. Check with the manufacturer to find out what filters will work with your furnace, or have an HVAC technician check your system before installing. Note that your air is cleaned only while it is moving through the filter, so keep your furnace fan running when air quality is poor. You may wish to upgrade to a higher MERV filter only during poor air quality events; discuss the wear and tear on your furnace and the potential for higher utility bills with your furnace manufacturer’s local representative.

Another option is portable air cleaners with true HEPA filtration, which can dramatically improve indoor air quality. These standalone units use a fan to pull air through a true HEPA filter (MERV rating 17-20), which mechanically removes the fine particles in smoke. Costs for portable air cleaners increase with room size. However, you should be able to find a good portable air cleaner with a true HEPA filter for under $200, suitable for most living rooms or bedrooms. Use the portable air cleaners in the room where you spend the most time; it is a good idea to run one in your bedroom while you sleep. Try to keep windows and doors to the room with the portable air cleaners closed to allow the machine to recirculate air through its filter. Make sure the portable air cleaner is sized appropriately for the room. Caution: mechanical portable air cleaners are reliable, while some that are electronic produce hazardous ozone (a gas) and/or other hazardous chemicals, and hence should be avoided (USEPAa undated, 2018a, 2018b, 2019).

For a lower-cost solution, you can put together a do-it-yourself fan/filter. Use a newer box fan (manufactured in the past five years), and a MERV 13 furnace filter attached to the back of the fan with the airflow arrow pointing toward the fan. Duct tape or a bungee cord will do the trick. Do not leave such a set up unattended, and change the filter when it becomes visibly dirty. These do-it-yourself air cleaners can be quite effective in rooms around 250 square feet. More information, including how-to videos, is available at montanawildfiresmoke.org.

- Reduce sources of air pollution indoors when poor outdoor air quality requires staying inside. For example, avoid burning candles, smoking tobacco, using aerosol sprays, or burning your woodstove or fireplace.

- Upgrade your woodstove or fireplace, as needed and if possible, to one that is tighter and cleaner burning, thereby helping improve both indoor and outdoor air quality. See the US EPA’s Burn Wise website[37] for tips in woodstove use and for links to the US EPA’s database of certified woodstoves.

- Support transitioning to clean, renewable sources of energy. As the American Lung Association states in its Lung Health Brief (American Lung Association 2016): “Switching to clean, renewable energy will allow the US to generate electricity without adding pollution that harms Americans’ health… Decades of research shows that these pollutants trigger asthma attacks and heart attacks, cause cancer, and shorten lives, among many other health impacts.”

Flood and drought

Flooding can contaminate surface water and groundwater, and harmful algal and bacterial blooms are expected to become more frequent in a warming climate. The trends of early-season runoff and late-season drought described in the MCA (Whitlock et al. 2017) can also impact food security and the incidence of vector-borne disease (also see Section 2).

Here’s what you can do:

- Protect your home from the risk of mold by checking for piping leaks or water accumulation under sinks, crawl spaces, attics and basements. Install drainage systems to prevent rainwater or saturated grounds from damaging your home, including providing a foothold for mold and rot.

- Act quickly if you find mold in your home. Along with the health effects that result from mold exposure—e.g., allergies, stuffy nose, wheezing—the longer mold grows the more damage it will cause to your home. You must both eliminate the water source and remove the mold. EPA’s A Brief Guide to Mold, Moisture, and Your Home provides a useful guide, including the tradeoffs between cleaning your home yourself versus employing a professional (USEPA 2012).

- Monitor your water supply if you have a well, and make your home as water-efficient as possible. These are good practices anytime, and potentially critical during times of drought. Store spare water in case of an emergency.

- Ensure your wellhead has a watertight sanitary cap, rather than an old-style cap with no gasket. The casing for a well must extend at least 18 inches (46 cm) above the natural ground surface; casing extensions can be added if needed (USEPAb undated). These features protect your home well water from contamination year-round, and especially in the event of a flood.

- Be prepared to boil, filter, or chemically purify your water before drinking in the event of flood contamination. Such treatments can eliminate most organic contaminants and microbes (USEPAc undated). Organic compounds can be the biggest concern during a flood due to sewage (human and/or livestock) runoff. However, those with wells should know—in advance via testing—if their water contains such inorganic contaminants as uranium, arsenic, manganese, or other hazardous metals or nitrates. In the case of flood, such contaminants might make boiling your water a poor idea as boiling will likely concentrate these inorganic contaminants, resulting in increased health danger. Uranium, arsenic, and some other hazardous contaminants have no taste, smell, or color—thus, you won’t know they are present until you have your water tested. Montana State University’s Montana Well Educated Program is an excellent resource for accessing discounted, EPA-certified, well-water testing for microbial, organic and inorganic contaminants, plus for learning more about drinking water quality and safety.

- Never swim in, nor drink from, water where blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) are visible or where harmful algal blooms have been reported (MTDPHHS undated). Similarly, keep pets and livestock away from waters where such hazards are present. If you are camping, understand that boiling, filtering, or adding purifying tablets to water will not remove these toxins. Public drinking water supplies in Montana are not required to monitor or test for cyanobacterial toxins (MTDPHHS undated). For further information, see Section 3 and the Harmful Algal Bloom Guidance Document for Montana (MTDPHHS 2019).

- Conserve water and reduce your water bill by upgrading to high efficiency showerheads, toilets, and washing machines, plus fixing faucet and shower leaks. Keep your grass at least 3 inches (7.6 cm) high, mulch your plants, landscape with drought-tolerant plants, and learn best watering practices. Know how to operate and maintain your in-ground sprinkler system most efficiently. You can find great tips and water conservation resources on the city of Bozeman website.[38]

Food security

The growing-season drought and limitation on agricultural irrigation water projected in MCA (Whitlock et al. 2017) will likely result in crop losses, lower yields, higher anxiety among producers, higher food prices, and higher risk of food-borne disease. Commodity crop and livestock producers can be challenged by a wide range of climate change factors, many of which are not local, but impact global food security. On a local scale, community food enterprises are taking an active role in growing, marketing, processing, distributing, and retailing food to decrease reliance on food vulnerability of global food systems. Building local food availability creates local jobs, improves the community economy, in some cases lowers emissions from transportation and storage, and benefits human health by providing more fresh and nutritious food (Norberg-Hodge et al. 2002; Borelli et al. 2020).

Here’s what you can do:

- Buy from local sources whenever possible, including farmers markets, community supported agriculture (often called “CSAs”), food hubs[39], and growers’ coops.[40],[41]

- Diversify food supplies and crop types. Plant and eat from a variety of food sources and eat more seasonal foods.

- Purchase less processed and highly packaged food.

- Learn how to prepare and store more foods for later use. Store non-perishable foods in a location expected to be safe and accessible in emergencies. MSU Extension is an excellent resource for helpful guides on food preservation and storage.[42]

- Plant and grow your own vegetables using organic fertilizer and an efficient irrigation system.

- Advocate for local foods—fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, or meat—sourced and processed in Montana.

- Decrease waste, both your own and your community’s, by supporting community compost collection.

- Support farm-to-table restaurants that use locally grown foods and ask others (including hospital cafeterias) to do so, as well.

- Encourage Montana’s farm-to-school program[43] and the FoodCorps program[44] to inform our teachers and youth about local food sources.

Vector-borne disease

Changing temperatures and water regimes are expected to expand the range of illnesses spread by vectors such as mosquitos, ticks, and fleas (see Section 3).

Here’s what you can do:

- Mount (or repair) screens on windows and doors to prevent mosquitos from entering your home. Limit pools of water around your home, where mosquitos breed.[45] To protect yourself outside use insect repellent and wear long-sleeved shirts and pants. Stay inside or take extra precautions especially at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active.

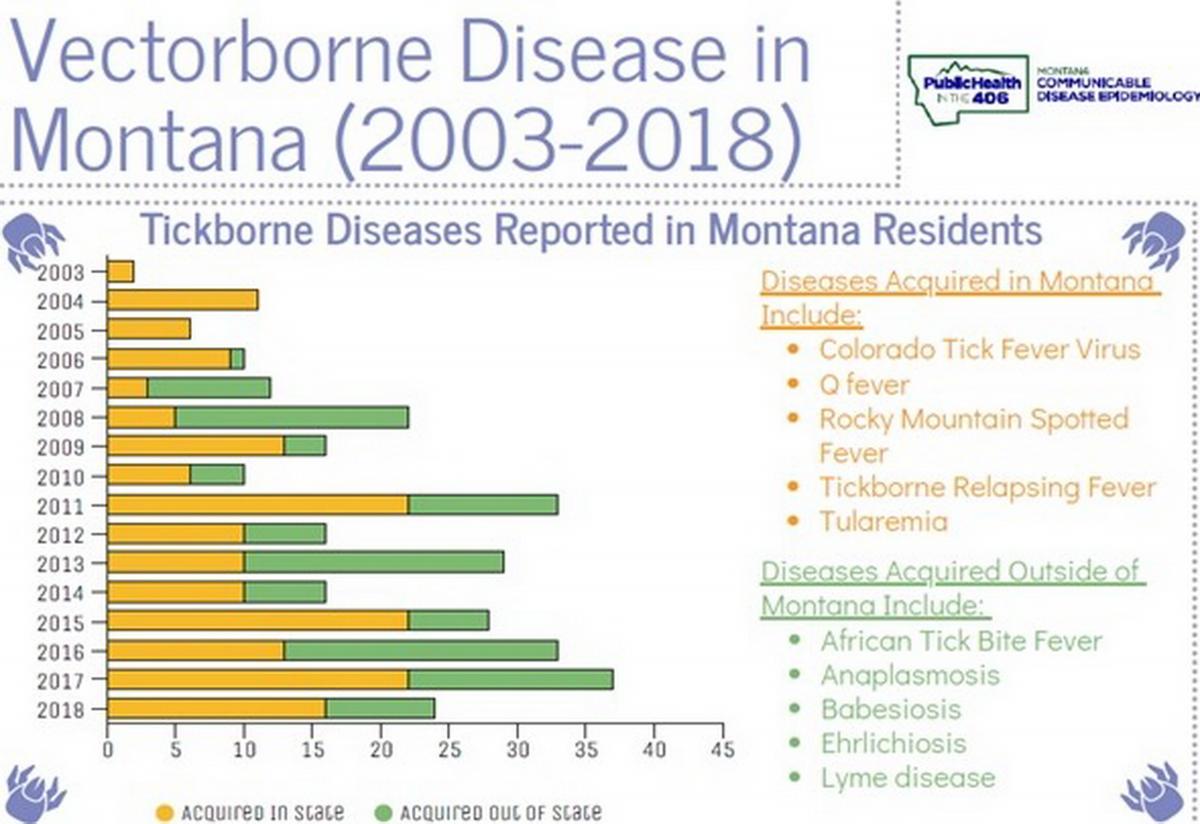

- Monitor outbreaks of vector-borne illnesses—e.g., West Nile virus, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and Q fever—through your local health department or the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services website[46] (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2. Summary of vector-borne diseases reported by Montana residents in 2003-2018. The figure is an example of vector-borne disease tracking that citizens can access from the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services website (start at https://dphhs.mt.gov/publichealth/cdepi/surveillance).

- Tuck your pants into your socks when walking through grasses or areas where ticks are common. Check yourself for ticks when you return home. Visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for further information on preventing tick bites, removing ticks, what to do after a tick bite, where different types of ticks live, and more.[47]

- Watch for potential emergence of zoonotic disease by monitoring the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services website (also see Section 3).[48] Although there are many illnesses that can potentially be transferred from animals to people, there is currently no research showing that climate changes are directly increasing these health risks in Montana. Still, new zoonotic diseases that emerge in other parts of the world can reach Montana, as COVID-19, from the SARS-CoV-2 virus, demonstrated (see sidebar).

Epidemics, Pandemics, and Climate Change

Epidemics and pandemics have ravaged human societies throughout history. However, studies suggest that the number of infectious disease outbreaks from all causes has increased significantly since 1980 (Smith et al. 2014). Up to 75% of newly emerging diseases originate in animals (referred to as zoonotic diseases) (USAID undated).

As the world combats the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, questions arise about the contribution of climate change to the emergence of new infectious diseases and pandemics, in general. Many of the same factors contributing to climate change also increase the risk of new diseases. Deforestation—for agriculture, urbanization, and mining—is a leading contributor to climate change due to the burning of trees and subsequent loss of carbon sequestration from photosynthesis, which further increases atmospheric carbon dioxide. In addition, deforestation forces humans and wild animals into more frequent and closer interactions through loss of habitat and increased numbers of people living at the forest edge (Faust et al. 2018; Bloomfield et al. 2020). This proximity increases the opportunities for disease transmission to humans. Deforestation, coupled with economic disparities and food insecurity, can also lead to more people hunting wild animals for food in many parts of the world. It also forces animal species that would normally occupy different habitats into close proximity to each other, yielding yet another opportunity for disease pathogens to cross species boundaries.

Warmer temperatures globally drive animals and plants to shift their range from unsuitable areas to places with conditions more conducive to their survival. This report discusses such shifts relative to disease vectors such as mosquitos and ticks, but research suggests that similar movement is occurring with mammals, such as bats, bringing them into new areas and increasing risk of disease transmission to humans (Plowright et al. 2015).

Along with potentially contributing to the emergence of infectious diseases, the burning of fossil fuels also causes air pollution, which worsens the effects of certain epidemics and pandemics among people with chronic medical conditions. During the 2003 SARS outbreak (Cui et al. 2003) and recent SARS-CoV-2 outbreak and resultant COVID-19 pandemic (Wu et al. 2020), virus-related mortality was highest in areas with high levels of air pollution.

Thus, climate change does not cause the diseases that result in epidemics or pandemics. Climate change can, however, amplify the impacts on human health, and even some of the factors that make pandemics more likely. Further, many of the drivers of climate change also contribute to emergence of new zoonotic diseases in humans. By addressing those forces, we not only lessen the chances of new diseases, but mitigate climate change, as well.

Mental health: getting involved and finding support

The stress of climate change can greatly influence our mental health. Recognizing that you need help and taking the first steps to process hard times is often the most difficult. Approaches to protecting mental health include crisis counseling, primary care intervention, individual and group therapy, and practices that increase emotional coping abilities (Hayes et al. 2018).

Here’s what you can do:

- Learn more about coping skills. If you can, seek advice from a mental health counselor, therapist, or another trusted support person.

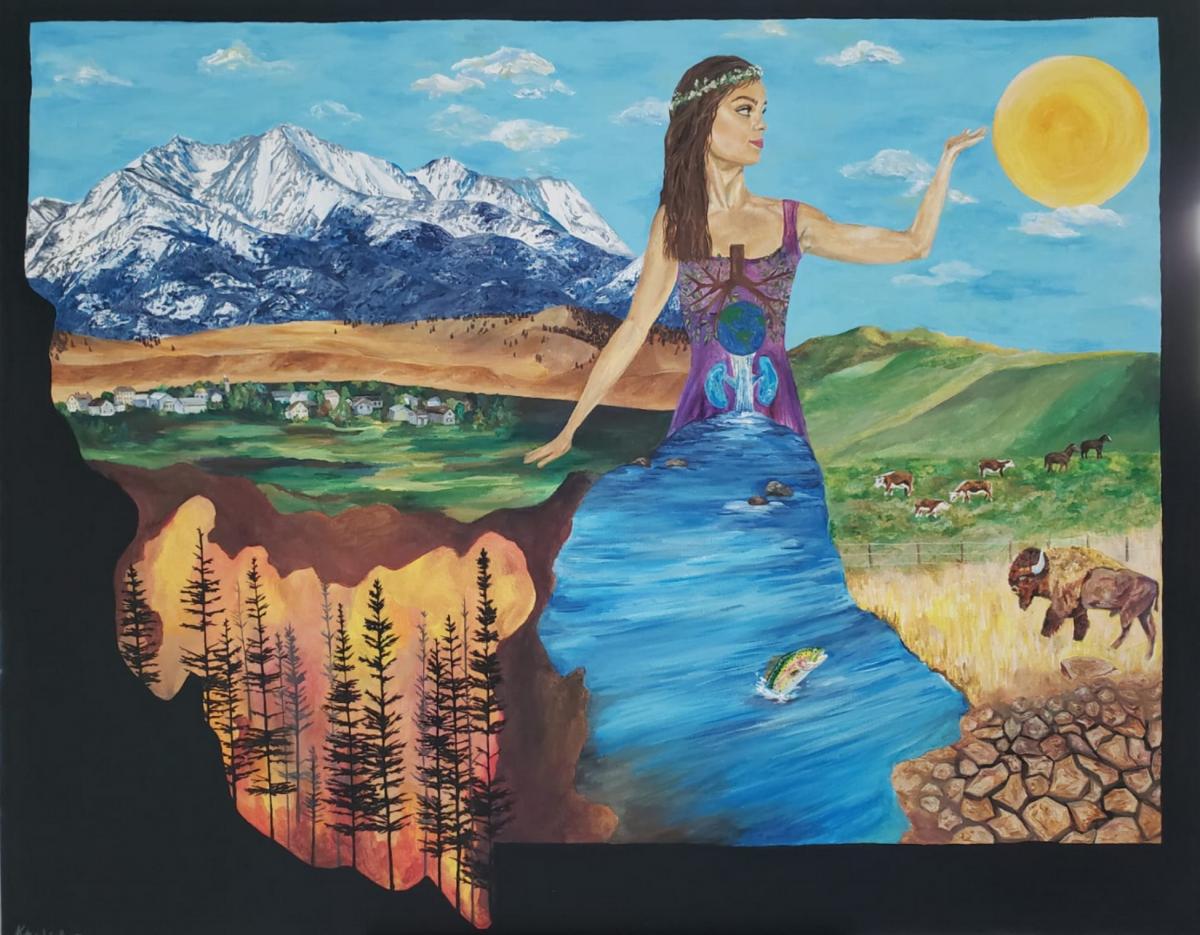

- Get involved with art, literature, nature, and spirituality; spend time with friends; get outside; exercise; garden—all will increase emotional resilience (Koger et al. 2011; Hayes et al. 2018; Guardian 2019) (Figure 5-3).

- Build a sense of community and become involved in civic action, such as volunteering, polling, voting, or advocacy. Working on climate change adaptation or mitigation has been shown to have mental health benefits (Reser et al. 2012), so find a group or organization that is active on climate change issues and get involved (see Table 5-1 and sidebars in this section).

- Foster optimism by maintaining connectedness to family, place, culture, and community (Clayton et al. 2017).